3 The Prehistory of Prestwood: before 1850

So it must have been after the birth of the simple light

In the first, spinning place, the spellbound horses walking warm

Out of the whinnying green stable

On to the fields of praise.

Dylan Thomas “Fern Hill”

Ancient Footprints

As a “new” parish, there are few obvious sources of information on the history of the area before its creation. Those there are, in the surrounding parishes from which it was carved, are still very limited, because for the bulk of its history this area lacked a community of any significant size or any important estates. Had the records of Peterley Manor survived there may have been more to tell, but as it is we have little to go on and must sometimes infill the gaps between the fragments of concrete knowledge in reconstructing Prestwood’s early story.

Like the rest of the Chilterns, Prestwood in early post-Glacial times would have been densely forested by a mixture of trees. Clues to the composition at different times are provided by analysis of pollen found in peat deposits, although most of these sites are some way removed from the Chilterns, so that we cannot be sure how far the results apply to our area. Birch, aspen, rowan and sallow were the first trees to re-colonise the receding tundra, about 11,000 BC. Hazel and pine followed about 8,500 BC. By 4,500 BC small-leaved lime was probably the commonest tree and there was also much hazel, elm, ash and pedunculate oak (Rackham 1986). Field maple was probably common too, but it sheds relatively little pollen and does not show up in pollen analyses. Neolithic people first arrived around 4,000 BC, at which time the amount of small-leaved lime and elm began to decline, whether from the effect of grazing, deliberate exploitation by early man or a wetter climate is unclear. Hornbeam was introduced around 3,000 BC. Beech was the latest arrival, about 1,900 BC and well into the Bronze Age. It increased rapidly on poor acid soils where competition from other tree species was low, but it only became common in our area on the chalk because of planting in medieval times, when, along with hornbeam and hazel, it was one of the trees of choice for creating wood-edge along boundary-banks. The earliest colonisers, aspen, rowan, birch and sallow had by now become only occasional trees, rather than woodland dominants and it was only in the last century that birch began to become more common again. Wild cherry became common only as a result of deliberate introductions for its fruit, while English elm was introduced in Roman times for vine supports.

Even before man began clearing trees from certain areas the forests were probably not continuous. Lightning fires would have created temporary clearings and the climate was far wetter than it is today, which limited tree growth along river valleys and even in depressions on the plateaux and hill-tops. There would also have been plenty of grazing animals like red and roe deer, aurochs (wild ox) and wild boar, the last two now extinct in Britain, the first two extinct in this area until roe were deliberately re-introduced a hundred years ago. These would have kept some of the forest relatively open, vital for many of the woodland plants and lower shrubs like juniper and guelder rose (and also providing routes of access for man). Along with smaller creatures, they also provided prey for predators long disappeared – the wolf, bear, polecat and pine-marten.

In Neolithic times man lived on the plains or on the crests of the Chiltern escarpment. The forested hills behind (i.e. to the south-east) were a wild land, used for occasional hunting forays, or gathering fuel and food like fungi and fruits. They would have been a vital resource but also a place of danger, and it is not surprising that few artefacts from that time have been uncovered in the parish. Only four are documented, in fact. One was a well-formed flint scraper found in a garden off Wycombe Road. Two were Neolithic axes - one discovered in 1930, and the other, a chopped-and-ground flint axe, unearthed in 1970 by a bulldozer driver working on the playing-field for Clare Road school. Finally, a Bronze Age flint arrow-head was found 20 years ago in a hedge at the top of Cryers Hill. I have also found scrapers nearby at Hampden Bottom and in the Misbourne Valley.

On the clays, ditching and "ridge and furrow" ploughing helped remove surplus water, making the swampy land cultivatable. Floodplains of rivers, prone to flooding in the winter, were used for hay, the water bringing in rich silt to produce a lush growth of grasses and other flowers, animals being grazed on the aftermath. Human settlements, with the concentration of stock, brought about areas of nitrogen enrichment, where blackthorn, hawthorn and elder, and to a lesser extent wild plum, buckthorn and spindle, were quick to colonise and become a more prominent feature of the landscape.

Flints with worked edges for use as tools by Neolithic settlers. Apart from sharp serrate edges made by chipping, the stones have also been carefully chosen so as to fit comfortably in the hand. The tool on the right seems to have been shaped for shaving arrow and spear shafts.

A prominent and puzzling remnant of Bronze Age times is Grim’s Dyke (or Ditch), a mysterious earthwork curving its way in three separate sections across the Chiltern Hills. The name handed down to us is Anglo-Saxon, but it was almost certainly coined then for a feature already in existence. The origin of the name is interesting. “Grim” (the origin of our current adjective) was from an ancient Indo-European stem meaning “wild” or “furious”. By association with the distorted countenance of fury, the same stem is exhibited in the old English “grima” or mask, the origin of our modern “grimace”. The same stem is associated with ancient words for “thunder” – the sound of the wild. Through this last notion, Grim came to be an epithet applied to the Anglo-Saxon god Woden or Thor, the “Thunderer”. Woden’s name is found directly in association with another ancient earthwork, the similar ditch Wansdyke that snakes across Somerset and Wiltshire. Woden was the most important god of the heathen pantheon, the one from whom the tribal kings among the invading Saxons all claimed descent. In postulating that only such a god could create this massive ditch, they were also laying down their stamp of ownership.

Leaving aside Saxon imaginations, however, the truth is more prosaic. It seems to have been simply a boundary between early Celtic tribes, two major ones of which came up against each other here. Unlike the ditches and ramparts familiar as defences for prehistoric hillforts, Grim’s Dyke was far too long to have been a viable defence – one could not possibly have watched its full length. The embankments are also of the wrong form to have had military use. In any case, there are many points where the ditch ends at a valley and continues further on so that by-passing it would not have been a problem. It is similar to the later Offa's Dyke in this respect, more symbolic than a practical barrier. If one was found on the wrong side, however, no doubt the consequences could have been serious, just as they still are today if an urban gang-member is discovered on the wrong housing-estate. That what it symbolised was of considerable importance is indicated by its prodigious size, especially taking into account soil creep, whereby all such ditches tend to become much shallower with time. Interestingly, the ditch keeps more or less to a single contour just over 200 metres, and it is thought to have marked the furthest northern advance of the Iron Age Catuvellaunian tribe that occupied the southern Chilterns about 300BC. Beyond was the realm of the hill-fort dwellers of the Chiltern escarpment, probably more primitive with more of a hunter-gatherer life-style. In a sense, then, this important line marked what was to the southern tribe, the limits of civilisation.

Grim’s Dyke can be traced on the ground today less than a kilometre beyond the northwest boundary of the parish of Prestwood, where it comes along from Great Hampden, but suddenly stops where a wood ends (Oaken Grove). Beyond here, however, an old track continues exactly in the same line and enters the parish to run into Honor End Lane, just beside an old pond. The path may mark where the ditch once continued, the earthwork itself being filled when converting to farmland. Whether this is so or not, here at Honor End Lane the line of the ditch comes to its final halt. One could speculate that the ancient way might have bent here, more or less following the natural contours, along Honor End Lane itself. No more trace of it, however, is to be seen until you cross right to the other side of the Misbourne Valley, well to the east of Prestwood, where it appears again at The Lee. Sheahan, 1862, records, with what justification I do not know, that “Grimesdyke” ran near Nanfans, an old gentleman’s residence by the side of Honor End Lane. It may then have continued along what is now the High Street and on past Andlows Farm, keeping more or less at the same height throughout. Certainly this route was a major track marked on the oldest maps. But this is speculation. All we can know for sure is that the only Grim’s Dyke in Prestwood today is the street of Gryms Dyke on the Council’s first post-war housing estate beside the recreation ground, named after a different ditch known locally (and probably jocularly) by that name, built for drainage in the late C19th on the enclosed common nearby.

Grim's Ditch at Hampden, only a shadow of its former depth

Roman Settlement

The Romans left very little impact on our area, with no roads or residences thereabouts. The Romans chose the valleys rather than the hills and the nearest villas are in High Wycombe and the lower Misbourne. It seems there were, however, farmsteads belonging to ancient British Belgic tribes among the woods on these hills at the time of the Roman occupation and for some time thereafter. A silver finger ring identified as being of that culture was uncovered in the Nanfan area in April 2005 by Tom Clark, who also unearthed a few Roman coins (one possibly C2nd; a likely forgery of Tetricus II 270-273; one minted in Trier, Germany, 308-309, for Constantine I; and a similar one from the reign of Constantine II 337-340). These indicate trade with continent at the time, but not a local Roman presence. By this time, in any case, the Roman occupation was in decline. A more significant find was a couple of bags of Roman coins of the usurper Emperor Magnus Maximus 383-388 (formerly a Spanish commander in Britain fending off invasions by the Picts and Scots), unearthed from a field not far from the centre of the parish some years ago. It is again unlikely that this represented a Roman hoard, but merely the continued use of Roman currency after they left by the semi-Romanised Belgic farmers. Unfortunately someone met an untimely end before they could retrieve their fortune. This fine collection of coins can be seen today in the County Museum at Aylesbury.

|

Coin of Constantine Great AD308-309 minted in Trier.

|

Obverse shows two soldiers bearing standards |

Probable coin of Constantine II AD337-340

|

Silver ring thought to be Romano-British |

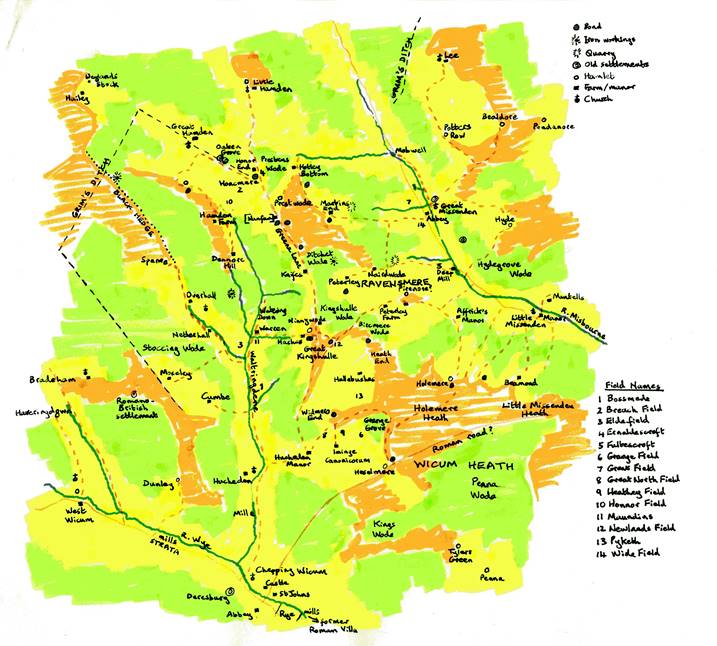

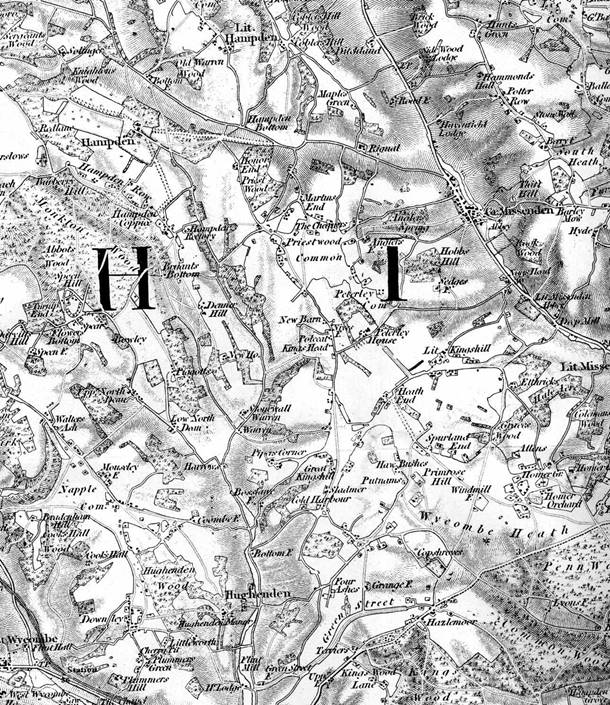

Map of Medieval Prestwood and surrounding district

The features on this map are no more than good guesses from limited information. Medieval names are given wherever possible. Land-use is indicated by green for woodland, brown for heathland, and yellow for agricultural land. The boundaries are vague and no more than suggestions of the likely extent of each. Main trackways are shown as dotted lines. The map is an amalgam of various dates, and is only meant to give an idea of the main features that would have been present in the early medieval era.

Anglo-Saxons

After the Romans left there was an interregnum in which rival Celtic- and Romano-British chieftains instituted kingdoms whose boundaries ebbed and flowed, but little is known about life on the ground. The Middle Saxons invaded along the Thames Valley and the West Saxons, coming from the south coast eventually held the territory south of that river, but they were slow to advance further north, hampered by the Angles invading through East Anglia and gaining control of the Midlands. The Chilterns occupied a borderland where British (Celtic) tribes remained dominant for a long time and the land was not, in the early stages of Saxon occupation, productive enough to waste re sources on. That they referred to this area as Cilternes, which is almost certainly a British name, is evidence that this region of denser woodland was for long seen as a British domain and the "last stand" of the besieged Britons, with their hill-top redoubts and seasonal pastures rather than permanent settlements. The meaning of this name is uncertain. Some have suggested it derived from a supposed Celtic word cilte or celte meaning "hill-slope" (the origin of the name Celt itself, for the "dwellers on the hill-top"). (See Potter & Sargent 1973.) On the other hand, the name may have referred to one of the main and most valuable products of the region - the omnipresent flint. Although the Celtic spoken by the British tribes is no longer known, clues can be obtained from survivals in modern Celtic languages. The word cyllell in Welsh means "a tool with a cutting edge (knife)" - a same term in Old Cornish is collel and in Breton kontell. Remembering that the cutting tools used by Britons were originally made of flint, it would have been quite likely that the same word would be used for both the tool and the material it was made from. (In Basque, a similarly ancient language, the words for "stone" haiutz and "knife" aizto are directly related; similarly the Old Norse hammer, origin of our modern name for the tool, meant "rock".) The old Celtic may even have survived in regional dialect to be adopted as a miner's term, now adopted as a general scientific term, "chert", for the minerals that include flint.

The Saxons, like the Romans, preferred the valleys, where water was permanently accessible, there was less wood to clear, the soil was more fertile, and settlements were more sheltered.

The only Saxon settlements of any size near Prestwood were those at Wycombe Wicum (970) and Amersham Agmodesham (1066). The former name is the dative plural of Anglo-Saxon wīc "settlement" and therefore means "at the settlements". This refers to the existence of two Romano-British villages at different confluences with the River Wye, what is now West Wycombe lying at the bottom of the Bradenham valley and High Wycombe at the bottom of the Hughenden valley. The fact that the Saxons used this name means that there were already settlements here before they arrived, and there was even a Roman villa just to the east of High Wycombe. "Amersham" is thought to have meant "Aehlmund's homestead", a Saxon name indicating that this was basically a Saxon settlement.

The first Saxon settlers in the vicinity of Prestwood arrived from Wycombe and Amersham, up the Hughenden and Misbourne valleys respectively. These valleys would have provided productive soil, woodland resources on the hills above, and most important of all, water. While both rivers were "winterbournes", i.e. often drying up or reduced to a very low flow in summer, there were various springs along both valleys that provided a constant source of water, the land being much wetter from a higher water-table in the chalk than nowadays. Both streams certainly began from further up than they normally do today. Their settlements in the Misbourne valley, Great and Little Missenden, are thought to have been named from "valley where marsh-plants grow" mysse + denu (Missedene Domesday Book 1086 is the earliest reference we have), so the fields by the stream to the east of Great Missenden must have been permanently damp, and this fact was significant enough to be enshrined in the name. The earliest mention of the river itself, as Misseburne, is as late as 1407, so that this is probably a back-formation from the settlement name - "Missen(den) river". (An alternative etymology might connect an early Celtic word for "field or flat area" (in modern Welsh maes) directly to the naming of the river, as the Misbourne Valley is strikingly flat from its origin spring at Mobwell downwards, and was laid to water-meadows and cultivated from early times, continuing into the farmlands run by Missenden Abbey in the Middle Ages.)

Hughenden is also first mentioned in the Domesday Book (as Huchedene) but the name tells us little, only that the valley denu here was made or claimed by a man called Huhha or Hycga. This name survived as Hitchenden from the C16 th right up until the C19 th , but became in Victorian times the present spelling, for reasons unknown except perhaps to assimilate the founder's name to the modern "Hugh". At the same time as these two settlements were made, or shortly after, other settlers probably moved from up the then tributary of the Misbourne that extended west from just north of Great Missenden further up into the hills to found a third manor named in the Domesday Book, Hamdena, which became (Great) Hampden, "valley with an enclosure" hamm + denu. While all these settlement names stressed their riparian locations, the original farms were almost certainly on the top of the slope above each valley, as evidenced by the location of the manor-houses of Hughenden and Great Hampden. Although the location of the original manor of Great Missenden has been lost, the parish church stands in such a location, high above the present village, and was probably close to the original farmstead, as was the case at the other two manors, these churches being the creations of rich landowners. That the first manuscript mention of all three manors is not until 1086 is indicative of these being quite late Saxon settlements of the C9 th or C10 th . (It should be noted that the original manor-house of Hughenden stood on the opposite side of the valley at what is now Rockhalls Farm, not at the present site, which was at that time a subsidiary farm within the manor.)

It is not certain when the first Saxon settlement occurred in the area covered by the present parish, but the land would almost certainly have been split among the three surrounding manors, probably more or less corresponding to the boundaries of the civil parishes today. So Hampden Manor would have included the north-west portions of the parish that lie above Hampden Bottom and Denner Hill on the west (an extension of Hampden Common); Missenden Manor would have claimed all the eastern half; while Hughenden probably included the southernmost portion, including what became Great Kingshill. The first Saxon settlements would therefore have been formed as satellites of these manors substantially later, although this does not preclude the prior existence of British farmsteads in this area. Indeed, the finding of pre-Saxon remains on Denner Hill and near Nanfan (see above) would suggest that there was such a presence at these locations at least.

The first Saxon settlements in Prestwood parish were probably satellite farms of the Hampden Estate and they almost certainly were at the same sites where a British presence is suspected. Indeed the estate may simply have asserted ownership and extracted tribute but left the original farmers in place. The name Denner first occurs in writing as Denore in 1241 and combines Anglo-Saxon denn or “swine-pasture” (i.e. mixed woodland-pasture) with ōra, “hill-slope” (see Gelling 1984), a common suffix in the Chilterns (cf. Chinnor, Stonor). It is unlikely to derive from denu, valley, as "valley hill-slope" would make little sense, although this is the suggestion of Mawer and Stenton 1925. Approaching from Great Hampden across the Hampden Common plateau the steep slopes plunging down each side of the narrow Denner ridge would have been notable. The prefix indicates that Denner was still at that time predominantly wooded, as well as indicating a major part of its economy. The hill remained well wooded up to the early C19th. Most of the field boundaries there were therefore late creations and cannot be used for hedge-dating to confirm early clearances, except the hedge alongside Rolls Lane giving access to the ridge from Prestwood, which is certainly a very ancient sunken lane. Another old hedge and associated bank running east from Dennerhill Farm probably represents a former woodland edge, as the bank is south-facing only and comes from gradual lowering of the land surface on the southern cultivated side. This may well represent early clearance of woodland to the east and south of the present Dennerhill Farm, the likely site of the original farmstead, which would have been built of wood and left no visible remains.

As for the original farm where Nanfan now stands, there is much less evidence to go on, as the present name is that of a Cornish family that acquired it in the 18th century, and the original name is lost. The main evidence for early occupation comes from hedgerow-dating (Appendix III), which throws up a cluster of thousand-year-old hedges in the Nanfan area, mostly south from the farm itself, all in the area covered by the former Nanfan estate (as it still was in 1850 before it was dismembered). The fields adjacent to Nanfan to the north were known to have been Hampden farmland, including fields such as Honnor, Breach and Ernaldescroft (lying between Honor End Lane and Lodge Wood) mentioned in early medieval manuscripts, so that Nanfan would have been a natural externsion of clearance, even more so if there were already a British farmstead there. (Any chance of further hedge-dating in this area north of Nanfan was long ago destroyed by the brickfields that were established there in the late C19th, although the western hedge-line of Ernaldescroft survives beside Honor End Road and is certainly ancient.)

"Priest's Wood" Preosts wudu (later Lodge Wood), also north of Nanfan, was part of the Hampden estate until very recently and was named as such because certain rights of usage of the woodland were granted to the priest assigned to the manor, who was established nearby at the farm called Honor End (C13th Hanora). At that time priests, provided by Missenden Abbey, had to provide for themselves through farming whatever land resources were allocated to them. The fields Honnor and Breach were assigned to Honor End, the name of the second quite possibly referring to this gift to the priest, if it derives from OE bryce "use, advantage, service". The name is another -ōra one, the farm being at the top of the same slope down to Hampden Bottom as Hampden House itself. The prefix is hān "stone", often used for "boundary stone". Although the farm lies towards the outskirts of the Hampden estate it is not on its boundary, but it is beside the parish boundary between Hampden and the detached portion of Stoke Mandeville at the point where Honor End Lane crosses it. On the other hand, "stone" may refer to Denner Hill stone, which was excavated from much of the land in this area and provided very hard building material of some renown (as suggested by Mawer & Stenton 1925). A large pond just to the south of the farm may once have been an extraction pit. Any boundary stone would have been made from this material in any case, so perhaps Honor contains a convenient double meaning. (The family Hono(u)r, mentioned in C14th century manuscripts and historically associated with Prestwood and its environs, has no known connection with Honor End, although Reaney, 1997, asserts – on what evidence we do not know - that the family name derives from that farm.)

Isolated farm settlements were also created on the north and east sides of Lodge Wood, in the valley at Hampden Bottom and on the hill-slope beside a narrow side-valley at Hotley Bottom. "Hotley" (?Otta, personal name, or hōd, shelter) appears to be an early form, but we have hardly any evidence for when either farm was founded. Hotley Bottom is directly connected to Nanfans (via the modern Greenlands Lane) and some hedges along here and also by the road down the side valley to Hampden Bottom appear to be ancient, suggesting an early date for both farms (late Saxon or early medieval). Both routes are deep "sunken lanes", further substantiating their antiquity. Just southeast of Hotley Bottom Farm is a very large pit which would have been used long ago for extracting chalk-rock for building and other materials.

The first clearances on the east side of Prestwood were mainly carried out by the monks of Missenden Abbey and are thus later than 1133, although some of the lands they acquired may have already been cleared. They established the former farm at Martin's End, first mention 1486. (Keen, 1980, suggests that Martin may have been one of the monks assigned to manage it; OE ende was used to refer to small outlying settlements, as at Honor End.) Another farm was created at Peterley. This assignment included "waste" to be cleared for farming, which may well have resulted from scrubbing over from a previous clearance. The trade of one prior tenant of land conveyed to the abbey, on the other hand, was "hunter", so one can assume that this was part of extensive woodland still well stocked with boar or deer. Keen (1980) rejects the proposition that Peterley represents “Peter’s field” (Anglo-Saxon leah “meadow”, a term usually used to represent clearings in woodland) because of the lack of the possessive “s”, and proposes that it denotes “stony” field from petro “rock”. The Anglo-Saxons used stan for rock. Petra, from the Latin, could only have been a post-Conquest term used by the monks, and this would be in accord with the date of its earliest mention in 1150. The ancient way from Missenden Abbey to Peterley was described as “Piterleistan” in 1180 and may refer to a boundary-stone stan here. The boundary of the late manor of Peterley ran along part of this lane. The valley along which this lane ran was known as "Groynesdene" (grynde "depression"), which may refer to its steep sides (although they are not exceptional for the area) or more likely to a large ancient pit where flints, chalk and chalk-rock for building were extracted. This pit survives as a scrubby dell and gave its name to the nearby Stonyrock Plantation. An old sunken lane (Hobbshill Lane) wends along the brow of the hill above Great Missenden, at the north end connecting with the old route from Missenden to Martin's End, and at the south end, Peterley itself. Hedgerows along various lengths are also ancient and indicate that not only would it have been an important link between the two Abbey farms in Prestwood, but that it may well have preceded both of them. After the Dissolution the track decreased in importance, becoming largely a means of extracting timber from Atkins and Hobbshill Woods, but it remained a prominent enough feature for much of it to be used to define the eastern edge of the new parish of Prestwood when that was drawn up in about 1850.

On the south side of the parish we know there was an early farm at Upper/Lower Warren and probably others along the valley coming up from Hughenden. The river here currently called simply the Hughenden Stream, which emerges well south of Prestwood at the bottom of the settlement of Hughenden Valley, was once much more extensive and emerged from springs to the west of Prestwood, including tributary streams along side-valleys. In medieval times this valley was known as "Wateringdene", i.e. "valley supplying water for stock". This is where the Hampden Road now runs and water runs here only after exceptionally wet times. This is a later form of English, like the names associated with the abbey lands, and indicates that settlement may have occurred post-Conquest, i.e. after 1066. The oldest farms are at Boss Lane (originally Bossmede, referring to a supposed name Bossa) and Upper/Lower Warren, that must refer to medieval rabbit warrens. An ancient sunken way, Boss Lane, connects the first farm along the side of a small valley to the Kingshill plateau, while another sunken way from Warren makes use of another small valley to reach Kingshill at Hatches Farm (below). The latter valley was known as "Ramshurst", almost certainly hyrst "wooded hill" and hramsa "wild garlic or ramsons". Some of the woods nearby are still characterised by large colonies of this plant.

Some clearance was made of side valleys where there were springs, but there would have been extensive woodlan d on the higher slopes along each side, much of which still survives today. That on the eastern side separated the valley from the plateau settlement at Great Kingshill (Kingeshulle 1196), on land that was probably settled after the Conquest. It was owned by the king, who assigned it originally to his kinsman Bishop Odo of Bayeux, who later forfeited it, the land returning to the Crown. A settlement here must have been associated with a major track from Wycombe northwards (now the route of a major A-road), indicating that a different form of settlement along the high plateaux was also occurring in early medieval times, associated with extensive trade routes, for this became a major drove road in later centuries along which many farms were formed on the west side of Prestwood. While valleys were earlier preferred for farm settlement for their access to streams, it soon proved possible to dig wells to water plateau land and travel would have been far easier here than along the boggy valley bottoms. The earliest farm at Kingshill was Hatches and the derivation of its name is ambiguous. While it may come from the Anglo-Saxon haecc, gateway into the forest (our word “hatchet” – for cutting down trees - comes from the same stem), the possessive "-s" makes it more likely to come from the personal name Hacce. The other major farm here, which was certainly rather later, was Ninneywood (Nynning 1540) has a similar ambiguity. It could be “Ninus’s Wood” or “the enclosure by the wood” from (n)innan “enclosure”. If the reference in each case was not to a personal name, both would indicate close proximity to woodland on both sides of Kingshill at the time of first settlement. The ancient ways between Kingshill and Boss Lane and Warren Farms show that the valley and hill settlements were probably formed at a similar time. Another farmstead north of Kingshill was also established along the same track from Wycombe at a similar time or somewhat later - Nives (from a personal name). This would eventually be the site for the new Prestwood Parish Church.

Putting all this evidence together (and it can only be suggestive rather than definitive) one can surmise that by Saxon times some of the old woodland had already been cleared for scattered farmsteads at Honor End, Nanfans, Denner Hill and possibly Hotley Bottom. Around the C12th, Peterley, Martin's End and Hatches were probably created (along with Warren and Boss Lane Farms just beyond the parish). By the end of the medieval period one could certainly add Ninneywood and Nives.

There is evidence, too, of the existence of heathlands (Prestwood, Kingshill), more open, scrubby country among the still dominant woodlands. These may have been natural clearings resulting from the marshy nature of the ground, coupled with low fertility and wild animal browsing that would have discouraged the growth of trees. Such clearings would have been used to pasture domestic livestock, further reducing the trees and shrubs and creating the heathland environment of heather and gorse that survived until the enclosures of the C19th(Chapter 9). Surrounding all these were major remnants of the ancient woodlands, probably still linked up and not separated into distinct “woods” as they are today (with the possible exception of Priest’s Wood). The Saxon farm settlements were probably small congregations of huts populated by single kinship groups, perhaps with some sort of protective fence. These would have been small houses of wood, probably combining human and animal living quarters; a mill powered by wind; and a small oratory. Inhabitants would have been largely self-sustaining: weaving their own clothes, making their own pottery, and working wood for furniture, fencing, instruments etc. Unlike many farm-systems in the lowlands, where “open-field” systems divided into unfenced strips worked communally were the norm, the fields in the hills were distinct enclosed blocs. Apart from cultivated fields, each settlement would have had to have access to a variety of resources – rough open pasture, woodland pasture, woods, and (vitally) springs for water. The peasant was basically a freeman (ceorl) – “essentially an individualist; owning the land which supported him, though farming it in association with his fellows, and responsible to no authority below the king for his breaches of local custom” (Stenton 1943).

Domestic stock (cattle, sheep, goats, horses) was driven from over-wintering arable land and hay meadows in spring to rough grazing pasture, and occasionally woodland. Swine were allowed to forage for acorns and beech-mast in the woods in early autumn (cf. the origin of the name Denner Hill, above). Grazing, particularly by pigs, prevented regeneration of trees and created glades within the woodland, the kind of environment still to be seen near Prestwood in those parts of Little Hampden Common that were not replaced by Victorian plantations. Deer (native roe and red deer; fallow were only introduced by the Normans to manorial estates) also grazed the woodlands, preferentially browsing ash, elm, hazel, hawthorn and holly, all of which became rarer in wood-pasture, while oak (whose young shoots contain bitter tannins), beech, hornbeam and aspen would have had a better chance of survival. Woodland was valued as an important economic resource, for timber (oak being the most valuable, but beech cheaper and more easily worked), hunting, fowling, collecting fruits (elder, hazel) or honey from wild bees, and harvesting firewood (mainly willow and gorse). It was therefore actively managed by the use of ditch-and-bank boundaries, reinforced by laid wood-edge trees along the banks to create dense "hedges" haga, so that stock could be contained or excluded at will, coppicing and pollarding (of almost all types of tree) to create slim timber for fence-posts, poles, wattle, furniture, wagons and baskets, and lopping of tree foliage as winter fodder to supplement hay or make brooms.

|

|

|

Ancient ditch and banks bordering Lodge Wood, with remains of laid wood-edge on top of the inner bank (right)

Such was the economic value of woodland that legal charters governed rights to hunt or gather wood, jealously preserving the rights of the lord of the manor to the most valuable timber, preventing over-use or mis-use for sustainable yields. In these times all buildings were of wood, and so was all fuel. Charcoal-making (using especially coppiced oak) was used as a way of increasing the calorific value of wood as a fuel. In some places iron-rich nodules were present in the clay in local pockets that could be mined and then smelted using wood from the forest. Remains of such local small-scale smelting can sometimes still be found (e.g. Piggotts Wood west of the parish, or Peterley Wood). Under such intensive use few trees would have survived more than 200 years, unless they were pollards, important boundary markers or other landscape features. The Romans had first introduced fruit-trees (domestic apples and pears, plums and cherries, grafting cultivated varieties on to wild stock, and orchards gradually became more common, especially on church land and close to habitations. Sometimes fruit trees were also deliberately planted in hedgerows of hawthorn and blackthorn as a resource. (See Hooke 2010; Rutherford-Davis 1982; Rohen 1968.)

The central Chilterns were at this time within the territory of the Middle Saxons (although this fluctuated continually as different groups battled for territory), which included settlements to the north of the hills (the Aylesbury plain) and south of them (the Thames valley), but the bulk of the hills were still one extensive forest with few settlements, stretching from the Goring Gap to Epping Forest and Colchester. The only major settlement was probably Hertford, far to the east of Prestwood, although minor ones existed at the edge of the escarpment, as at Wendover, and along valleys like that of the Wye (Chepping Wycombe) and Misbourne (the Missendens). (Their place-names commonly used the suffix –ing or “people”). The Chiltern forest was used for hunting forays by neighbouring kings, especially from the London area. The Danish invasion of the C9th led to settlements more or less to the east of the line of Watling Street, and thus did not affect this area. It is thought that the native British people may well have survived for a long time in small farmsteads in these hills, away from the more easily worked lands of the valleys preferred by the foreign invaders, who avoided heavy clay soils needing excessive capital in oxen, sturdy ploughs and slaves. The finding of a Belgic ring near Nanfan reinforces the supposition that the first settlement in Prestwood was British rather than Anglo-Saxon. That the "Chilterns" took its name from Celtic reinforces the presumption that there was no major invading population on the higher ground. That Wendover, close up to the Chiltern escarpment itself, was an old British (Celtic) name meaning “white waters”, seems to have the same import. Unfortunately, unlike Saxon, few Celtic place-names have survived, those that do mostly referring to rivers.

The Domesday Book of 1086 was a detailed and fairly inclusive catalogue of all land in England, compiled for William the Conqueror for tax purposes. Unfortunately Prestwood gets no direct mention here, being at that time too insignificant a settlement. The account is ordered by district (hundred) and land-owner. The land at Prestwood and Great Kingshill was then divided between several holdings, split between three different hundreds (Desborough, Stone and Aylesbury). While we cannot identify Prestwood land, the account of the local manors at Hughenden, Missenden and Hampden, which would have included it, can still be used to provide some glimpse of rural life at that time.

Hughenden, in Desborough Hundred, was then part of the huge estate of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux (the king’s half-brother and the major Buckinghamshire land-owner, with 26 manors), and held from him by William FitzOgier. Here ten “hides” were worked. (The “hide” was the basic unit for tax assessment, but it could be rather variable in size. It was supposed to represent the amount of land needed to support one “household”, which is also difficult to define, but probably meant an extended family of three generations, which would have been the normal social unit at the time.) One hide is equivalent to anything from 40 to 120 acres, and in any case it was a purely notional concept as used in the Domesday Book, with no attempt to attain equivalence among local variations in the definition of the term. FitzOgier’s land would thus have amounted at most to about 1,200 acres. If one notes that even the small parish of Prestwood, only a fraction of the size of a district like Hughenden, is 2,000 acres, then the amount of “worked” land in 1086 must have been only a small proportion of the whole territory, which would still have been dominated by uncleared woodland, unlike the better agricultural land along the Thames Valley to the south or on the Aylesbury Plain to the north. Whether or not the assessors’ data included outlying farmsteads such as we suspect had already made isolated clearings in this extensive woodland, we cannot tell, but given the short time they had to make their report and their obvious concentration on the main villages, it is possible they were overlooked as trivial from the point of view of taxable value. These farmsteads may therefore have preserved a certain degree of political independence, albeit tenuous, as they would have been living at no more than subsistence level.

As lord of the manor, FitzOgier would not have worked his land directly, the estate being divided among fifteen “villans” (villagers) who were subjects of the manor, along with three “bordars” (cottagers of lower status) and five slaves. (Apart from the slaves, these figures refer to households, not individuals.) Before the Norman Conquest (when the land belonged to Edith, Edward the Confessor’s queen), the villans (quite possibly Celtic British) would have been beholden to Saxon lords, even though it was their forebears who had cleared this land. They merely changed one master for another. (Many slaves were part of the spoils of war, others descended to that status through poverty or crime. They were the property of their owners, to be bought and sold, and their status was inherited by their children. They might be hung for running away or burned for theft. Feiling (1966) refers to “slave-girls who carried water in yoked buckets or ground at the mill.”) These households worked ten “ploughs” of arable land, a plough being another variable measure of area, the amount that could notionally be maintained with one eight-oxen team. It was roughly the same as a hide or two, but used for a different purpose, as a measure of production rather than taxable value. One fifth of the produce of these crops was paid to the lord of the manor. There was also meadowland of two “ploughs” producing hay for the animals and a certain amount of woodland used for agricultural purposes. During Anglo-Saxon times this would have been mainly devoted to the pasturage of pigs, and so the custom had grown of measuring the extent of a wood by the number of pigs it could maintain. Although by Norman times it was thought that this practice had been largely discontinued, the measure was still in use, so the Domesday Book records Hughenden as having woodland for “600 pigs”. It is difficult now to give any estimate of what sort of acreage this might have been, but it was probably of the order of four “ploughs”.

The Bishop of Bayeux also owned “Hanechedene”, corresponding to “Hitchenden”, the north-eastern part of today’s parish of Hughenden that was later also known as “Brand’s Fee” (see below). This would have included what is today Great Kingshill and land on the west side of Prestwood, reaching almost up to Nanfan. This area was held from the Bishop by Tedald, but the account adds that it is “now of the king’s farm”. This was probably Hatches Farm at Kingshill. The area of Hanechedene for tax purposes was just three hides, but included seven ploughs, and would therefore seem to have been more intensively cultivated than the rest of Hughenden. One sixth of the area, with two ploughs (even more intensively farmed) constituted tribute to the lord of the manor. There were at this time six villans, three bordars and five slaves. Before the Conquest the Saxon ownership of this area was said to be split between two men. One was Fridebert (2½ hides), who owed allegiance to Leofwine, Earl of the London shires - including Bucks - and East Anglia. Leofwine was a brother of King Harold, fighting with him at Hastings, one of the few Anglo-Saxon earls whose power had survived the Danish conquest by Canute. The other was Alric Gangemere and his sister (½ hide), and the Domesday Book records their complaint that this land had been “unjustly taken from them”.

Great Missenden, in Stone Hundred, was the property of Walter Gifford, counsellor to the king himself, and a major landowner, who had 48 manors in the county. His son (also Walter) was the first Earl of Buckinghamshire. Great Missenden was leased by him to Turstin fitzRolf, and it was assessed like Hughenden at ten hides. There were eight ploughs of arable land (two owed to the lord), two of meadowland, and woodland for 500 pigs. This was worked by 9 villans, 1 bordar, and two slaves. This land had been held, under the Saxons, by a “thegn” (lesser nobility than an earl) of King Edward, one Sigeraed, a son of Aelfgifu. Aelfgifu was the common-law wife of Canute and had remained powerful in the royal household even after the king’s official marriage to Emma of Normandy. She was appointed regent of Norway in 1030 on behalf of her and Canute’s son Swein, who was still in his minority. Another of their sons, Harold, was briefly to become king of England (1036-1040).

The third estate, which would have included a small part of north Prestwood, was that of Hampden in Aylesbury Hundred. The owner here was William fitzAnsculf, another substantial landowner with 16 manors in the county. It was held by Otbert and comprised just three hides, with five ploughs of arable, and woodland for 500 pigs, worked by four villans and two slaves. The rents of the woodland were said to amount to enough iron to make two ploughs! (Iron may well have been worked locally using naturally occurring accretions in the clays and the abundant timber to feed the kilns, as lumps of crude iron have been found near old workings in local woods - see Chapter 2.) Before the Conquest, this land had belonged to Baldwin (possibly the same Baldwin who was abbot of Bury StEdmunds), a man of Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury (who had been raised to that seat by King Edward and was deposed by William, replaced by a Norman bishop).

What can we learn from this? It is tantalising in its detail and attempted quantification, when the measures employed are so vague and difficult to interpret. What was missed? In other areas the Domesday Book sometimes recorded mills, pastureland and other features, but we get only the bare bones here. It was probably just not productive enough from a national economic perspective to be worth spending too much time on. Just 20 years after the Norman Conquest, the situation on the ground (for all the wholesale usurpation of ultimate ownership) must have been pretty much as it had been in Saxon times. The number of slaves (a quarter of all the households recorded in the four estates) reminds us of the brutality of this age – the prevalence of warfare and the cheapness of life. The rule of King Edward (only succeeded by King Harold II on his death in January 1066) was not sufficiently extensive and systematic to impose law and order, which relied extensively on self-help, kinship support and old customs. The fear of disorder was matched by the savagery of punishments. Under William civil order was to be attained at the price of loss of freedom and independence through the feudal system.

The number of households, just 55 across four estates, shows how thinly populated the area was around Prestwood/Great Kingshill. There must still have been extensive unworked lands, presumably still wooded for the most part, although some of these woodlands would have been greatly thinned by the demand for timber and the need for space to pasture animals. These pastures would have been barricaded by banks and ditches and already developing into the heathy grasslands with trees, heather and gorse scrub that probably characterised the wide hill-top commons of later centuries. Rackham (1986) estimates 26% woodland at this time for the whole county of Bucks, but the Chilterns were much more wooded than the rest, and the figure for this area would certainly have been over 50%, perhaps almost as high as the 70% estimated for the Weald in Sussex, the most densely wooded area in 1086.

We get no mention of tradesmen – blacksmiths, bakers, etc. Cottagers at this time had to be entirely self-sufficient, supplemented only by what surpluses they could trade (and trading networks at this time were surprisingly extensive – not only all over England but across Europe too, as the archaeological finds above attest). This is also exemplified by the rents for woodland in Hampden, where iron stood in lieu of cash.

Post-Conquest Development

The Norman manorial-based feudal system, however, was to increase security and

allow settlements to spread from their original dense enclosures. Thus the

skeletal pattern of Saxon settlements was significantly enlarged, with

additional farms and cottages spreading around the commons, associated with

strip meadows at Great Kingshill, down the west side of Prestwood Common, and

at what was the incipient hamlet of Prestwood along Greenlands Lane, with Kiln

Common at their backs. The last two communities were the basis for the

Prestwood community of the future. Remnants of parallel boundary ditches in

the southern part of Peterley Wood may also indicate similar strip fields there,

the cleared fields having been later allowed to return to woodland. By

medieval times, too, Andlows Farm (held by Richard Anlowe until 1488, when it

was inherited by his son John) had been established in a more isolated position

north and east of these earlier developments, implying the parallel development

of new routes across the north side of Prestwood Common and east down the hill

to Great Missenden.

By the time we reach the medieval era, therefore, the area had already become a patchwork of fields, woods and commons much closer to the picture that greets one today: the wildwood was being tamed. Soon the wolf, the boar, the aurochs, the red deer would all be gone, if they were not already. Carving fields out of the forest, their boundaries would have been left to trees and shrubs that eventually became hedgerows separating the fields, their origin made obvious by the fact that they still harboured (and still do so to this day) the old wildwood flowers – bluebell, dog’s mercury, yellow archangel, wood melick, green hellebore, moschatel and foxglove. Unworked woods close to the farms would gradually lose their timber to building and fuel, while domestic cattle, horses, pigs and goats would be left to pasture there, gradually converting the high forest to scrubland and more open heathland where only prickly gorse and unpalatable bracken survived. At the same time ponds were dug to water the beasts and wells to water the humans. The fields themselves provided pasture for sheep, pigs and cows, the first two particularly on the higher chalk downlands, the last in the rougher marshy areas. The remaining woodland was by now broken up into distinct patches that gained their names from neighbouring farms (like Nanfan, Angling Spring and Peterley) or adjacent fields (like Longfield and Meadsgarden). Small orchards were planted to provide fruit for domestic use. Geese and chickens scratched around in the farmyards, while goats were tethered on nearby grass. Smaller cottages clustered close to the commons, and their fuel and grazing resources, and to the farm estates that provided work. Each cottage would also have had its field strips for domestic production of food. Nothing remains of these older buildings today because they were built of wood – of which there was an abundant supply from the felling of the woods.

Very little evidence remains today of medieval strip-farming, most strips having been aggregated into larger fields. "Lodgewood Field", west of the eponymous woodland, remained as separately-named strips oriented east-west until the late C19th, and were part of the land allocated, like the wood itself, to the use of the priest to the Hampden Estate at Honor End. Old roads, too, sometimes wind, apparently unaccountably, as they passed the rounded headlands left by plough-strips, each wide enough to turn a plough in a semi-circle at the end. There is some remnant of this along Hampden Road, but the best example is the southern end of Hobbshill Lane, shown clearly in the following photograph.

Remains of medieval plough headlands along Hobbshill Lane

The extent of woodland fluctuated with the population, which at this time was subject to massive swings, due to devastating diseases like the Black Death. Sometimes clearings were made for agriculture and then abandoned again (as at Peterley Wood, see above). Their remains can be seen as areas within current woodlands where internal boundary-ditches are marked by gentle outward down-slopes created by the gradual subsidence of the soil through cultivation. These contours survive even when the field returns to high forest. An example can be seen at the lower end of Angling Spring Wood, just outside the parish.

The major farms were those attached to the manors and these were quite advanced in their agricultural techniques even in the Middle Ages. As Roden (1969) has it:

" This was best exemplified in the quality of ... demesne, with elaborate manuring, the early appearance of a three-course rotation, and controlled grazing within large enclosed fields. As in other parts of medieval England demesne cultivation became increasingly complex in character, the relatively simple cropping and pasturing techniques of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries being transformed in the fourteenth century into elaborate and flexible routines in response to changing socio-economic conditions. ...

"In the central and south-west Chilterns, in particular, the larger and older farms lay along the valley bottoms and lower slopes, centres of early settlement and cultivation, where some of the best soils are located and water supply was less of a problem; while the smaller farms of minor manors and monastic granges were often situated on the ridges and plateaux above, where late assarting [ forest clearance for agriculture ] had been concentrated. ... (This well describes the local situation, with the main farms and manorial lands in the lowland surrounding Prestwood - Hampden Bottom, Misbourne Valley, Hughenden Valley; while Missenden Abbey had lands by the river they expanded by establishing minor farms on the Prestwood plateau - Peterley, Martins End.)

" A majority of farms consisted almost entirely of arable land with very small areas of permanent grassland, either meadow (suitable for hay) or pasture. ... [O]n some demesnes it was frequently necessary to import hay to feed the stock in winter .The greatest areas of grassland were in the parks, already very numerous throughout the region, but these were often devoted to beasts of the chase and only occasionally entered the local farm economy. Meadow after mowing, patches of poorer grassland along the floodplains, and pasture closes on the upper dip slope (perhaps on land unfit for continuous arable cultivation) provided grazing, yet on many manors permanent pasture was limited to small closes and orchards near to the farmsteads and to hedgerows, greenways, and roadside verges. ...

"Although common wastes offered extensive grazing ... the quality of their pasturage was generally poor, they were shared by lords and tenants alike, and larger wastes were inter-commoned by a number of townships [ e.g. Wycombe Heath, shared between Kingshill, Hazlemere and Holmer Green ]. Private woodland was not normally used for grazing other than swine pannage, partly because herbage was limited by shade and partly because flocks and herds would have damaged valuable timber. ...

"The shortage of pasture ... underlines the importance of crop production as the basis for demesne farming. On all manors for which medieval grange accounts survive income from grain sales usually far exceeded that from the sale of livestock and their products ...".

The main crop on the better soils was wheat, on poorer ones a mix of wheat and rye. Other crops were oats (which became less popular in the C14th), barley, pulses and vetch. Soil condition was maintained by various practices - marling with excavated chalk (Missenden Abbey used chalk from a large quarry at what is now Stonyrock Plantation for its fields at Peterley), resting periods (fallow) once every three years with crops of legumes to concentrate nitrogen, and manuring with dung from cows and horses (sometimes gathered from the trackways) or leaf-litter.

Sheep were the dominant livestock, for wool and cheese, but flocks were usually small and varied from year to year. Cattle herds were also small (averaging 20), used for cheese and butter. Pigs were quite numerous and the main source of meat.

Almost all land was owned by someone, at least nominally. Although one talks of commons, these were not always the property of the local community, but might only imply traditional rights of local villagers to the use of certain benefits. These rights in Anglo-Saxon times were referred to as bōte, “compensation” or “relief” (from bōtian, “to make better”), that is, an allowance granted by the owner to enable the villagers who worked his land to survive. These might include rights to remove underbrush or the poles created by pollarding and coppicing, for fuel and fencing, to fell a certain amount of small timber for building and equipment, or to graze a certain number of animals. Where grazing allowed the development of open woodland-heath, gorse and heather might be cut for fuel, while dried bracken was also useful as bedding (both animals and people) and thatch. These grew into customary rights that had something of the force of law, reinforced by manorial courts, but ultimately they could be taken away, as indeed did happen at the time of the Enclosures (see below). The commonland on Denner Hill was of this kind (part of the Hampden estate). Neither Prestwood nor Great Kingshill Commons, however, were ascribed any ownership in the Tythe Map (Part I). It seems likely that both were land excluded at the time of the Domesday Book as original woodland outside the claimed boundaries of any of the surrounding estates. Their gradual clearance was probably a result of post-Conquest expansion of settlement, with each new cottage associated with further clearance for its domestic needs.

Rackham (1986) describes the typical “wood-pasture common” of these times:

…grassland or heather with more or less thickly scattered trees and bushes. The grass was grazed by livestock ranging from horses to geese. Trees were cut for firewood and sometimes timber. The normal practices were pollarding, in order to produce repeated crops of wood (or occasionally leaves) without the animals eating the regrowth.

The survival of heather until recently among the trees in the top half of Lodge Wood shows that this was almost certainly maintained as wood-pasture. As the shade of the trees grows, this heather is dying out. Already the stagshorn clubmoss that grew there with it has become extinct, as it has done for all these former wood pastures. Similarly gorse has become very infrequent, when once it would have been a defining feature of this wood pasture. It survives particularly, although tenuously, in Lawrence Grove, that had been hedged with bank and ditch (it was formerly part of Ditchet Wood, a much larger wood that included Peterley Wood and many surrounding areas that are now fields). Much of the common land in Prestwood has been built over in modern times, but some outliers of the kind of heathy grassland that would have developed on these commons can be seen in Hay Pole field beside Hangings Lane (where betony and devil's-bit scabious uniquely survive in the parish) and in Widmere Field on the south edge of the old Prestwood Common, where harebell, pignut, slender St John’s-wort and common bent-grass still grow.

Growing organically from isolated farmsteads, linked by ancient trackways, some of them deeply sunken “holloways” grooved by centuries of traffic, this area lacked the traditional “village” until relatively late. This scene is what Oliver Rackham (1986) termed “Ancient Countryside” as against the “Planned Countryside” of nucleated villages, open fields, and few woods, heaths or hedges, typical of the Midlands or East Anglia. The impact of man is less evident here (although appearances are deceptive), the view more haphazard and changing, which gives the Chilterns (like Sussex and Kent) their special character and appeal. The difference runs right back to the geology of the chalk hills, with their soils of low fertility and awkward gradients, that shaped, just as it was shaped by, the activity of man (cf Roden 1965).

The outside world hardly impinged, and when it did for the purposes of trade, there would have been no surprises – the same developments, the same way of life, was going on throughout this rural area, only tenuously affected by the growth of towns in the major valleys several miles away. After the Norman Conquest the land was gradually parcelled up among lords (castles), knights and bishops (the principal players on the chessboard after the king and queen), but the Prestwood plateau, relatively undeveloped, remained a backwater. Here there were no parklands or royal forests to attract the nobles and to invite the building of their country seats. Between Missenden Abbey to the east, Hampden House to the north-west, and Hughenden Park to the south-west this remained a place of extensive woodland, isolated farms and tiny groups of cottages and developing commons for the labouring man.

The Manor of Great Hampden was created after the Norman invasion for Baldwyn de Hampden, and remained with that family until 1741. An Augustinian Abbey was founded at Great Missenden in 1133 by the Norman nobleman William de Missenden and collected a number of grants of land from the local landowners. The first mention of Prestwood in the Abbey records was some ten years after its founding. These grants, including much woodland as well as fields and uncultivated scrub, ranged from the north of the present parish (granted as a residence and living for a priest to serve the Hampden Estate), down through Peterley and Great Kingshill, possibly much of the eastern half (including the first clearances for Ninneywood Farm).

For instance, in 1161 William’s son Hugh de Nuiers (Noers) "gifted" (in return for a certain annual rent) “a virgate [c.30 acres] of land in Peterley with the addition of woodland, offered on the altar by token of a box-wood rod” (Jenkins 1938 v), land that had previously been held by a blacksmith. (Box wood is very hard and durable, and probably symbolised a long-lasting pledge. It was possibly prevalent in the chalk woodlands at this time and still forms whole woods just north near Chequers. The mention of a blacksmith is interesting - it means that we are now beginning to get specialist trades-people who were not solely reliant on subsistence farming, a sign that village populations had reached the critical level that enabled such division of labour.) This gift probably included the land where Peterley Manor was built, as this seemed to be central to the Abbey’s subsequent holdings in this area.

In 1190 his son Hugh the Younger renegotiated with the Abbey for the return of some of this land. In compensation, the Abbey was allowed to enlarge its holding at Peterley by “all the woodland to the north of their land in Peterley” (presumably Peterley Wood), “a certain portion of land which belonged to Rodulfus, the priest”, and “the land between Hugh’s wood near Peterley and the Abbey’s wood, called Kokkes Wude, 12 acres of land and 7 perches” (Jenkins 1938 iij). It is consistent with the geography to speculate that “Kokkes Wude” (named after the then tenant William Coch – Vollans, 1959) could be the presently named “Crooks Wood”, and the 12 or so acres of additional land would then have been what is now called Crooks Field, recently allowed to revert to woodland, but originally cleared land.

Another Frenchman, Faramus de Boulogne (or Faramus of Wendover), between 1158 and 1184, gave further recently enclosed land “hedged and ditched”, plus 4 acres “in front of the houses of Durwin and Elwin the hunter” (another specialist trade). Some of this land would seem to have already been cleared by the monks, for the documents describe it as “the whole land of Peterley which they have enclosed by dyke and hedge … which formerly had always lain waste, uncultivated and without return.” This would imply that the woodland here had already been cleared at some time, but the land left fallow for pasturing animals, or arable fields that were eventually abandoned and left to revert to scrub (i.e. “waste”). The legal transfer was therefore a regularisation of what had already occurred de facto.

Faramus’s daughter Sibilia married Ingram de Fiennes, who confirmed the sub-letting of recently enclosed and hedged land at Peterley, and in 1184-91 added fields and woods between “Prestwude” and Piterleistan. These woods probably included a swathe to the east of Prestwood parish, represented nowadays only by separated woods such as Angling Spring, Atkins, Hobbshill etc. It was through the northern part of these woods, through Angling Spring, that the Abbey was granted a right of way for carts from their base at Great Missenden to their holdings at Martins End. The track, which followed what is now Whitefield Lane and the present bridleway past Andlows Farm (and led further across the north side of Prestwood Common to Nanfans and what is now Honor End Lane) was therefore an ancient one. Connecting as it did at Honor End with Grim’s Ditch it may even have marked the now-vanished eastern extension of that prehistoric boundary. (District boundaries were often followed by trackways, as they provided routes that did not cross private property.)

Land conferred to the Abbey at Honor End is mentioned in documents of 1170-79, confirming a grant by Alexander de Hampden of a “virgate” of land there (probably about 30 acres), at least three fields. These lay north of the line followed by a boundary-ditch running through “Waltringden” to a boundary stone on Grim’s Ditch, east of “Hoacmer”. This was in fact part of the boundary of the Hampden estate, and the monks were obliged to lay a hedge along the top of this dyke to make the boundary clear and prevent animals straying. Hoacmer (Anglo-Saxon ac, oak, and maere, boundary) refers to the present Oaken Grove, probably the western end of the grant of land. Waltringden (waeter, water, and denu, valley) refers to the valley now occupied by Hampden Road, where springs then supplied water year-round and sometimes a stream ran down, where now is only a dry valley that only rarely floods when the water-table is exceptionally high. The boundary dyke met this valley near the old rectory and was used to mark the boundary of Prestwood parish when this was laid down in 1849.

The monks were allowed to pasture animals (100 sheep, 10 oxen, 10 cows, 40 pigs) on common land (belonging to the Hampdens) beside their holding in Lodge Wood (then known as Priest’s Wood) and fields neighbouring the wood (Breach and Honnor Fields), while the Hampdens retained the right to pasture on the granted lands when not in crop. It is therefore apparent that the monks’ holdings were intended primarily for arable use. Lodge Wood, as pasture-woodland, must have already had a boundary ditch and bank, with the wood-edge shrubs laid to make a hedge, to prevent the escape of stock on to arable land. The remains of this ditch system still remain around most of the wood, which has therefore retained most of its original shape. The Abbey was later granted full common rights in Lodge Wood and in 1227 Reginald de Hampden conveyed common rights for 100 sheep between there and “Fildenisse Maneswey”(“fields next to the public way” i.e. along Hampden Bottom, the route from Missenden to Hampden) and Prestwood. (See Hepple & Doggett 1994, p81; Vollans, 1959.) This may have been the location of Hotley Bottom Farm, which still kept sheep in the middle of the C19th.

That the lands gifted to the Abbey are mentioned as being previously occupied or worked by other individuals confirms that some land on the Prestwood plateau was being farmed before the C12th, although between them and the Abbey itself, built beside the Misbourne in the rich soils of the river valley, would still have been a substantial tract of forest on the steep slopes difficult to cultivate and therefore left uncleared (including the terrain of “Elwin the hunter”). It is likely, however, that these farms were relatively impermanent, with clearings being farmed for a while, becoming unproductive and left to become “waste”, and later worked once again. Only increasing population pressure resulting from the relative stability of the Norman occupation led to these less productive lands becoming permanent settlements.

Kingshill obtains its name from the fact that this manor was forfeited by Odo of Bayeux to the Crown, and it is mentioned in a manuscript in 1196 as “Kingeshulle”. At this time the region was owned partly by Faramus of Wendover, succeeded by his son-in-law Ingram de Fiennes, and partly by Geoffrey of Hughenden. Those holding the land from them included Geoffrey of Kingshill, Walter of Wycombe and Robert, clerk (priest) of Kingshill (the son of a smith). Part of Geoffrey of Kingshill’s land was 1½ virgates (roughly 45 acres) including a house at what was later to be called Old Field or Old Hill, and is now Lower Warren Farm, just outside the SW corner of Prestwood parish. This was part of Faramus’s land and had previously been rented by Eustace de Betun. Geoffrey had to pay 23 shillings per annum for this land. It was enclosed by a dyke and fence and there was a right to obtain brushwood and stakes for fencing from the “wood of Kingshill”. Geoffrey also held meadowland, arable fields and a grove in the region east of Great Kingshill, between lands held by Richard Sperling (who gave his name to Spurlands End) and Michael Mantel (whose name is still remembered in Mantles Wood at Spurlands End). These lands were adjacent to Peterley, as a manuscript from before 1217 makes clear, when the Peterley estate is described as “all the land and wood of Peterley on both sides of the Peterleystan Road; on one side as far as the land of Richard Sperling and that formerly of Geoffrey of Kingshill [i.e. as far as what is today called Heath End], and on the other as the tenements are bounded by dykes and fences”.

These holdings of Geoffrey of Kingshill are substantially removed from the previously mentioned ones at Lower Warren, implying scattered pieces of land across a wide area rather than a cohesive “estate”. This is reinforced by records of other transactions between 1220 and 1242, when Geoffrey transferred a number of pieces of land to Robert of Kingshill, including:

1. a strip in “Maldefurlong” neighbouring Robert’s land. [Later “Maundins”, this field was part of Lower Warren; from Middle English marlede “fertilized with marl (or chalk)” and “furlong”, a common name for a field based on the length cultivated by a plough – furh “furrow” lang “long”. Maldefurlong may have been an open field divided into different strips under separate ownership.]

2. a grove in the “Ramshurst” valley “by that of Matilida de Espele”. [ Originally “Raunneshurst”, itself from hraefn “raven” and hyrst “wood on a hill”, the latter still a common component of place-names ending in –hurst today. The wood here was what is now called Longfield Wood and its extension north, each side of the valley up which Perks Lane now climbs, which would then have been the site of the “grove” (a partially cleared or coppiced wood) in question. It does, however, reveal the existence of a bird at this time that can generally only be seen in the west of Britain, although it has in just the last few years started to appear regularly in our area once more.]

3. another strip in “la Forelithe”, also beside Matilda’s land. [Perhaps from forlerð “head-land” or land with furrows at right angles to those in adjacent land.]

4. a fenced close between Eldefeld [Old Field or Old Hill, the site of Lower Warren Farm itself] and the road from the head of “la Puhtule” to “Brekham” [braec “strip cleared for cultivation” and hamm “enclosure”] via “Wilekinesfeld” [welig “willow” and feld “open field”, obviously a marshy site, probably watered by a spring in a tributary valley to Waltringden, the valley in which Lower Warren Farm was situated; this may have been that followed now by Hatches Lane].

5. part of a meadow at “Schadewell” [scead “boundary” and wiell “spring”].

6. a bytt “small piece of land” in “la Wrothelithe by Wrothehege” [possibly hriðer “oxen” plus “land” and “hedge” respectively].

These references are tantalizing because their geographical locations can only be guessed at, but they are all quite small parcels of land in the Lower Warren area. They do, however, show evidence of strip farming in open fields at this time, although various enclosures are also mentioned, attempts by landowners to limit common rights of pasture. They also demonstrate the importance of water, in the mentions of access to springs (no longer in evidence along that valley except in periods of winter flood, when for instance the existence of a spring towards the top of Perks Lane becomes evident). Thus Robert was later allowed to enclose his land in Maldefurlong, but Geoffrey nevertheless expressly retained the right to draw water at “Maldeputte” [pytt “well”] in this field.

Robert added these transfers to other land he already held in the same area and also in the Spurlands End region, including part of a wood beside a road then existing from Birchmore [beorc “birch” , maere “boundary” – i.e. the boundary of Kingshill Heath marked by birch-trees; modern Birchmore Wood at Heath End] to Hazlemere and High Wycombe, this road called “Horserugge” [hors “horse” and hrycg “ridge” – perhaps because it followed the edge of the valley that ran via the modern Primrose Hill to Hazlemere].

Towards the end of the C13th (1277-79) Hugh de Plessis of Missenden granted some woodland close to the “gate” of Peterley Manor (this was possibly part of Nairdwood, later Shrubbery Wood c1840, a southern extension of Peterley Wood on its east side ), and “a piece of land situate on the south, next to Nairdwood, for the purpose of making a dyke between the said wood and the fields adjoining Peterley from the great marl-pit at Groynesdene up to the piece of ground before the gate of Peterley” (Jenkins 1938 xxxij). “Marl” here simply refers to chalk, frequently excavated in this region for fertilising fields, the pits often to be seen today in the fields, because at 5 metres or so deep they could not easily be ploughed out. This particular pit was alongside what is now Nags Head Lane, just west of Stonyrock Plantation. This modern plantation may then have been part of extensive woodland extending south to Sandwich Wood. This ditch (“dyke”) would have been a boundary marker, both a means and a symbol of enclosure.

These holdings at Peterley were close to others granted in the late C13th in the Kingshill area, such as parts of Denefeld (later Dean Field), Porinfeld, and “la Niweland" (later Newland) from Geoffrey son of Geoffrey Taylifer. The monks were granted the right to build another dyke, five feet wide, beside a hedge from Kingshill to the croft where Agnes Lennuere lived, along the whole length of Kingshill Heath to a grove at Newland. This may well have run from near Ninneywood Farm to the east of where Stag Lane runs today, a route still followed by a local authority district boundary, although no track or ditch remains.

While it is difficult to discover the boundaries of the Abbey’s lands from these descriptions without accompanying maps, based on long-forgotten names and features no longer surviving, it is clear that separate holdings existed at Honor End, Peterley and Martinsend in Prestwood parish, and the Abbey records do provide some picture of the land in medieval times. It was plainly already a patchwork of:

· woodland (a source of timber for fences and houses, charcoal, and, if enclosed, common grazing for animals), left on the steeper uncultivatable slopes (“hangings”) and the less fertile uplands;

· “assarts” - plots of land cleared, drained and enclosed for crops, hay, or the pasture of sheep and cows, some open fields worked by different land-holders (only in the wider valley bottoms), and others enclosed; and

· areas of “wasteland”, largely cleared of trees but still rough, undrained and as yet uncultivated, or formerly tilled and later abandoned.

All these were crucially marked by boundaries – lines of trees, banks and ditches, hedges and marker stones – and ownership in these early years was both changing and vital. The creation of fields would have involved much hard physical labour to turn the originally marshy scrub to land that could be cultivated. It involved the construction of drainage ditches, laying hedges, and breaking up the heavy stony soil of the “clay with flints” with wooden spades or primitive ploughs pulled by oxen. North of the Peterley holdings there developed an area of common land, still present in 1850 as Prestwood Common, where there were general rights of pasturage for horses, pigs and goats, and collection of furze for fuel. Connecting all these holdings was a network of paths and tracks. A few were more substantial, like those from Birchmore to Wycombe down the east side of Kingshill Heath, from Honor End across Prestwood Common and down to Missenden (traveling along the south ridge above the difficult marshes of Angling Spring Wood), Peterleystan connecting Peterley to the Abbey, and the road south from Prestwood Common to Wycombe (then referred to as the “London road”, an alternative to the route from Wendover through Great Missenden). While some settlements remained no more than farms – e,g. Honor End, Hotley Bottom, and Peterley – others slowly grew, at Martinsend, Prestwood Common, Great Kingshill, and Little Kingshill, although never rivalling the settlements in the fertile valleys like Great Missenden and High Wycombe. For all the changes in ownership that occurred over the centuries, this basic pattern set in medieval times survived largely unchanged up to 1850.

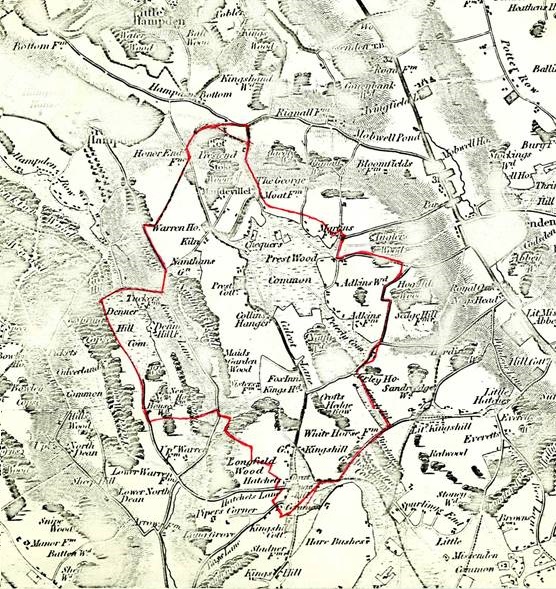

An important part of Prestwood parish was Kingshill Manor, which had been granted in 1252 to Sir Robert Brand as a "knight's fee" (i.e. land granted by the king in return for knight service) and held subsequently by his son John. This region became known as "Brand's Fee" and was known as such until the early C19th. Covering Great Kingshill and much land to south, the manor included a long tongue of land going north along the west side of what is now Wycombe Road and extending to the far north corner of Prestwood Common and west to what is now Hampden Road. So all the properties on west side of Prestwood Common. and including Collings Hanger and Knives farms to the south them, were considered to be part of Brand's Fee, not Prestwood, and remain to this day in the administrative parish of Hughenden.

|

Medieval button |

Spur C15-16 |

Finds unearthed at Collings Hanger Farm