11 Boom and Bust, 1950-2000

Nature is out of date and GOD is too;

Think what atomic energy can do!

Farmers have wired the public rights-of-way

Should any wish to walk to church to pray.

Along the village street the sunset strikes

On young men tuning up their motor-bikes…

John Betjeman “ The Dear Old Village ” 1954

Peace, then, dawned in 1945, to the sound of months of special celebration parties (Keen 1995), on a parish that was still visibly rural, with the fresh white blossom of fruit trees in spring. “At Prestwood … the cultivated cherry tree still holds its own” Massingham wrote in 1940. People noted swarms of colourful butterflies and the golden heads of corn in high summer. Wild flowers still abounded in the fields where birdsong greeted the sun. A good number of the old common ponds still survived, although their loss of economic function spelled their eventual ruin in most cases. Particularly large ones were Sheepwash, Wibner Pond off Hotley Bottom Lane and that beside Hatches Farm, where the children went ice-skating in the winter. Even when it rained it was not so difficult to travel as it had been fifty years before when there were no surfaced roads. The increase in housing and population meant a more thriving community and economic opportunity, without taking away the perception of Prestwood as a village. Wendy Doel (née Taylor), who was born in 1942 at Anchor Cottage on Honor End Lane, remembers it in this way:

Life was idyllic then, everything was much calmer and more relaxed and there was a real sense of community. Everybody used to work locally and socialise together in the pubs and village hall, which was the hub of village life. The old boys, as we called them, used to meet up at ‘The Chequers’ and play bowls on the green that used to be behind the pub.

The cherry orchards at Anchor Cottage were sold for grazing in the 1950s (they were eventually built over), but they were still important in 1950:

We grew White Heart cherries, which are dessert cherries, and also black cherries which were used in pies and for bottling etc. There were no fridges or freezers in those days so the cherries were preserved in kilner jars by topping them up with water and putting them in the oven. My granny used large wooden trays in the oven to stand the jars on. They were then put in the larder and the rubber seals kept the fruit from going off. Everything was grown organically as there were no pesticides. To keep starlings off the cherries, milk bottle tops tied to the trees, clackers and a scaring gun were used. In Stevens field a man fired a gun all the time after the cherries had ripened.

John Parker remembers as a boy at that time working for his grandfather at Hampden Farm as a bird-scarer, using a special home-made wooden rattle. (Personal communication.)

Wendy continues:

We used to have to pick before the birds stripped them. Very tall ladders were used to reach the top of the trees. They were so tall that to lean them into the tree was a two-man job, one holding the bottom rung down, whilst the other pulled the ladder over into the tree. My granny was still picking cherries when she was 75 years old. We always had cherry pies and granny used to make cherry wine as well. During the cherry picking season, there was always a cherry pie supper at the chapel. Everyone brought a pie along and we enjoyed them together. (Doel, 2000)

Even in 1950 there was no mains water in many cottages like Anchor Cottage, which still relied upon its well, doubling as a cool place in which to keep milk, butter and even ice-cream. Other cottages had an underground tank that collected rainwater from the gutters and drainpipes (eg Pankridges and Denner Farms).

There were also as many little pubs as ever, despite the closure of The George (an independent house) above Hotley Bottom in 1902. The King’s Head and the Traveller’s Rest were both recently rebuilt. The pubs and village halls were frequent meeting places and centres for social activity. Participation in local sports was high, with football (Upcommon and Downcommon teams played on ground by the Greenlands Lane allotments) and cricket teams, bowling on the green behind the Chequers, sledging on the fields in the snow. The Kingshill Cricket Club was still using part of the old Kingshill Common for their matches, as they do to this day, although it was not until 1935 that the pitch had been properly laid and 1957 before a pavilion was built.

Social activities were still regularly organised by the churches, schools, Women’s Institute, and a multitude of youth organisations. (Apart from scouts and guides, there were youth clubs in both Prestwood and Great Kingshill at this time.)

There were a great many shops, while many goods and services, including groceries, were also delivered to the door, as one resident remembered (Holy Trinity Church, 1999):

The Miller man from Risborough delivered grain for the people who kept chickens and rabbits. Milk, bread, meat and fish were delivered to the door. There was a Paraffin man, Muffin man, and sometimes an Onion man. Ice cream and soft drinks were also delivered. One of the most popular was the Pedlar man. He sold combs, ribbons, cottons, tape and elastic, and best of all, fancy hair slides and brooches as well as pins, needles, hat pins and trimmings. The Rag and Bone man would weigh the old clothes before offering a 1d or 2d.

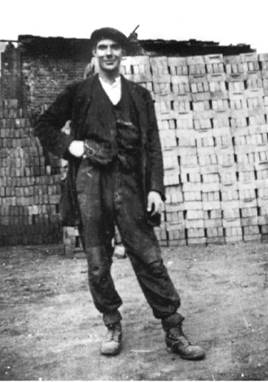

It may not sound so long ago – less than a century – but the photograph of Mr Buckland at Howard’s brickyard in the 1930s, turning up for work in jacket, waistcoat, fob watch, cloth cap, and trousers tied above the boots summarises pictorially the gulf between then and now in ways words cannot express.

Great changes were, as Bob Dylan was to say early in the 1960s, already “blowing in the wind”. Despite some rationing still being in force in the aftermath of the most debilitating war the country had ever known; despite the fact that the British Empire still featured in school textbooks as vast swathes of pink across the world; despite the fact that culturally the people had hardly moved on from the world of the thirties; despite a relaxed pace of life that made shopping, for instance, a social occasion rather than a chore to be hurried through; despite all this inertia, a much more modern era was now about to dawn and lifestyles were about to change more radically than they had ever done in any previous half-century.

The power of the working classes had been shown in the growth of the unions and of the Labour Party. (As early as 1911 Emily Stevens was remarking on the “Great Railway Strike” that was “ very bad in London, Liverpool and other places and the trains were stopped for two or three days .” She also notes a “great Coal Strike” in 1912 “ which was very bad for the poor people who only bought a little at a time ” and brought some trains to a standstill. Strikes came even nearer home in 1913 when “ The Wycombe chair factories people came out in December. About 4000 men and women out of work .”) It would not be long before the British Empire would cease to exist. The USA and Russia had now emerged as the new superpowers and the world was under the shadow of the atomic bomb, the creation of which the world war had stimulated. The Korean War was now beginning, a new type of conflict foreshadowing the Cold War and the Iron Curtain. Britain could no longer consider itself to be the centre of the world. The Council of Europe had just been formed in 1950. The iron and steel industries had just been nationalised by the new Labour Government under Clement Atlee. Universal education was now established. George Orwell had just completed “1984”. “South Pacific” was first performed in 1949. The old certainties were passing. Traditions that had survived the centuries were on the verge of being swept away by a scientific and technological revolution that undermined the confidence of the individual and the potency of Britain as a nation on her own.

Development

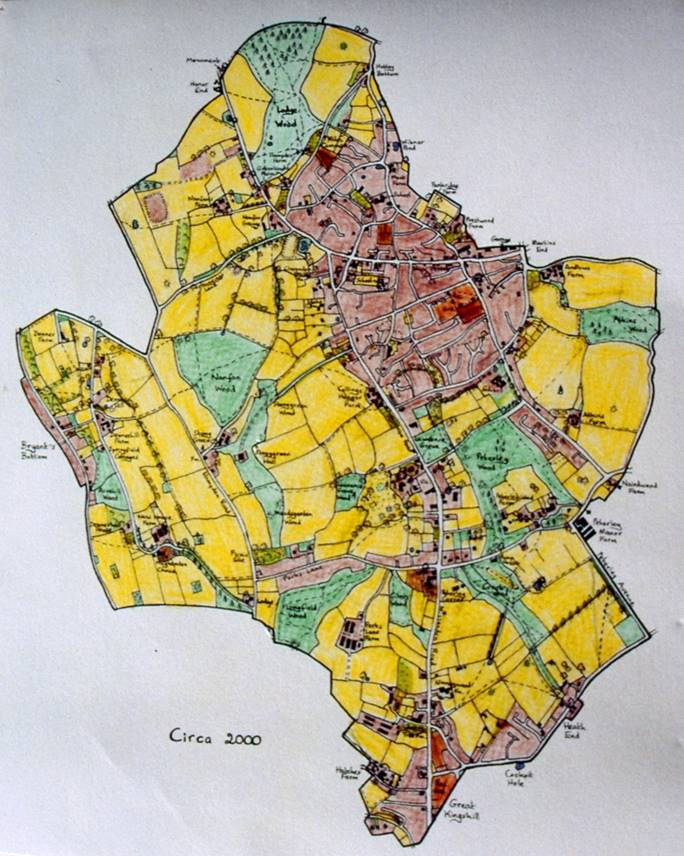

The building boom witnessed in the first half of the C20th was repeated in the second half, with a doubling of the land-area of the parish that had been converted to housing. By the year 2000 the number of houses was over 3,000.

Prestwood Parish 2000. Brown = housing or rough land. Yellow = agricultural land. Green = woodland.

This building, which was concentrated in the first 25 to 30 years after 1950, was confined to extensions of the existing built-up areas, with a particular expansion upon the former Prestwood and Kiln Commons. The greatest concentration of new housing was the ‘Lovell’ estate (named after the builders) that created continuous housing from the High Street to the former southern edge of the main common (now represented by the back garden boundaries of the houses on the southern side of the new road Lodge Lane, named after Prestwood Lodge at its eastern end.) Collings Hanger Cottage at the western end of Lodge Lane was knocked down at this stage, although the ancient Donkey Path which started from here and crossed to the middle of the High Street, being a public right of way, was preserved as a footpath, continuing also across the High Street to Moat Lane as ‘Brummagen Path’. (Another major route across the common, from the former Golden Ball to Martins End, was also a right of way, but became a road – first Sixty Acres Road, after the former field it crossed, and then Honor Road - only its far eastern section after Nairdwood Lane remaining a footway.)

The narrow belt of common that extended to the east of Peterley Wood as far as Nairdwood Farm was also converted entirely to housing except for the last couple of fields at the south end. The area north of the High Street was built up entirely as far as Greenlands Lane and the southern part of Hotley Bottom Lane. Wycombe Road became a continuous double row of houses from the High Street to Lodge Lane and from the Church south to Peterley Corner. The remaining space between Nairdwood Lane and Green Lane was all built up. Smaller amounts of new housing also completed the circumscription of the remnants of Kingshill Common. Building in the last couple of decades of the century consisted mostly of infill of the last remaining green patches amongst this sea of housing, including the development in 2000 of the Nutshell, a small strip of scrub just south of the High Street, that, despite being surrounded by housing, still contained an active badger sett, now abandoned, and remnants of an orchard (still present).

The Lovell Estate, built in the 1960s-70s was planned imaginatively, with many circuitous cul-de-sacs, a multitude of walkways criss-crossing it (including the preservation of the Donkey Path) and some green spaces. Some of the rows of houses were built with access roads, and their garages, at the rear, thus creating a green outlook and front door access by path only. A row of trees (mostly oak, with some ash) that once marked the south-west boundary of the common, planted when that part of the common was enclosed in the early part of the C19th, was preserved along Westrick Walk and Greenside, where they were set apart from traffic and enhanced the scenery for residents and pedestrians.

Modern house on Lodge Lane, part of the Lovell Homes development, built 1979.

Old Prestwood Common boundary oaks along Westrick Walk

This line of trees is important historically, scenically and environmentally and some are well over a hundred years old. Their preservation, however, is problematic because, surrounded by housing and in a warming climate, they could be in danger of drought stress. Some have already been lost, including one (an oak infected by Root Rot) that fell on the roof of a neighbouring house in 2010 and caused some damage. While many residents appreciate the trees, others are concerned about the safety issues, which may constitute a further threat to the trees.

While pre-war housing developments had allowed gardens of a quarter to half an acre, post-war building was at much higher density with handkerchief-sized gardens. The increase in population necessitated the inclusion of a new school, Prestwood Junior School in Clare Road. All this new building inevitably involved losses. Most of the tiny fragments of common land that had survived since the enclosures (as allotments and recreation grounds) were preserved, although part of the Kiln Common allotments was built over. Four allotments still exist in Prestwood parish - Greenlands Lane (Kiln Common), Chequers Lane and Nairdwood Lane (in Prestwood), and Kingshill Common (Great Kingshill).

Greelands Lane allotments - Prestwood Nature's demonstration wildlife garden 2016

Chequers Lane allotments 2007

Nairdwood Lane allotments 2007

Most of the building took place on agricultural fields and former orchards. The former were not in any case the most fertile, being on the relatively poor soil of the sandy clay, and the orchards had lost their profitability, particularly in competition with imported fruit, which was not limited to English seasons. The loss of the orchards was particularly dramatic, because they had mostly occurred on the fringe of the older housing and were therefore the first recourse for new building. Byrne (1967) records that the orchards had almost entirely gone by 1967. No longer can one enjoy the spring outburst of white blossom that was once such a feature of the parish, nor the cherry-pie feasts that followed harvest. Small patches of orchard by Andlows Farm, Collings Hanger Farm, Greenlands Lane and the Polecat are largely all that remain within the parish, although a new community orchard devoted to preserving traditional old local fruit varieties was founded by Prestwood Nature in 2008 on ground that includes the Greenlands Lane allotments (and still belongs by an anachronistic anomaly to Stoke Mandeville and Other Parishes Charity).

Orchard at Andlows 2000

Orchard at Collings Hanger Farm in the 1950s

Orchard at The Polcecat 2006

Orchard at west end of Greenlands Lane

Planting the new community orchard 2008

Building and road-laying also lowered the water-table in the more concentrated areas each side of the High Street, significantly affecting the few remaining common-land ponds in the area, which are now unable to maintain water sufficiently long through the year for the development of tadpoles, once numerous, including the Brickpits Pond off Nairdwood Lane, the pond in the Chequers Lane allotments, and that at Kiln Corner. What should have been amenities for local residents have turned into a source of concern and complaint at their poor state. Other ponds, even beyond the built-up areas, also continued to decline through their loss of economic function. The largest in the parish, adjoining Hatches Farm, was filled in entirely in 1964 (Byrne, 1967), losing the parish one very rare plant (Star-fruit) now nationally endangered, and a number of winter-visiting water-birds.

Sheepwash Pond on Honor End Road was also in a perilous state until Prestwood Nature restored it in 2007 with grants from the Chilterns Conservation Board and Great Missenden Parish Council. This was a historic pond because of its association with the old drovers' road and important for the wildlife it once supported. It is now a scenic spot, with benches and viewing platform, enjoyed and valued by many local residents, especially those living in the nearby sheltered housing at Giles Gate, although it has suffered from frequent vandalism that has become an unfortunate feature across all open spaces close to housing.

Sheepwash in the 1930s.

Across the road, through the gate, can be seen part of the orchards, including that behind Anchor Cottage, now built over

Sheepwash as it had become by 2007. Photo by John Priest

Sheepwash after restoration in 2011, the viewing platform at left.

Gorse flowering in the foreground arose naturally from long-buried seed

Nowadays the remaining countryside around the Prestwood and Great Kingshill developments is classified as Green Belt. Green Belt was introduced in 1955 in order to “ provide a reserve supply of public open spaces and of recreational areas and to establish a green belt or girdle of open space ” around London (Greater London Regional Planning Committee, 1935). Designation by the local authority as green belt is meant to

· check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas;

· safeguard the surrounding countryside from further encroachment;

· prevent neighbouring towns from merging into one another;

· preserve the special character of historic towns; and

· assist in urban regeneration.[From Wycombe District Council Advice Note 15.]

Within designated green belt it is intended to be difficult to get permission to build. Green Belt may, however, be re-designated from time to time by the local authority, often in response to demand for further housing. Designation may therefore be an obstacle to development, but it in no way guarantees that the existing countryside will be preserved. There have been several building developments around Prestwood on land formerly designated as green belt.One current green space in the Green Belt particularly threatened with becoming a development site is Widmere Field, and a neighbouring old orchard remnant, on the south side of Lodge Lane at its western end. Apart from Holy Trinity churchyard, it is the sole surviving example of the old acid grassland once typical of Prestwood Common and has a unique ecology for the area (although it has suffered from neglect). This is probably the most important green space in Prestwood from an environmental point of view and should really be a priority for conservation for wildlife, with appropriate management, and for public access. The land is owned by a developer and there have already been planning applications. These have to date been turned down, but the threat still exists and meanwhile neglect of the land continues.

A planning application for a house on the west side of Wycombe Road, at Idaho Cottage, is another current environmental threat, as it would involve the destruction of an ancient common-land pond that supports a large population of great crested newts, the only remaining site for this species in Prestwood. The pressure to build more housing nationally, consequent on increasing population, continues to be a major problem for preservation of the environment in the area. The environment is unfortunately low on the priorities of local district and county councils.

Another intended protection of the local countryside is its inclusion in the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) since 1965. This should entail positive management of the area to conserve and enhance the landscape, along with its wildlife and cultural heritage. Resources to manage the AONB, however, are very restricted and its impact on the ground locally has been minimal.

For all the changes that have occurred to Prestwood since 1850, in terms of population, economy and technology, the basic geographical structure has survived virtually intact. The main thoroughfares, the field boundaries, the woods – most of those present in 1850 can still be discerned clearly today, even though they may have changed in form: a field become a housing estate, a narrow track become an asphalted road, or an old hedge reduced to a spaced-out line of mature trees. The sunken lanes between high banks that indicate routes well-established even in medieval times are such firmly-etched contours that they are virtually ineradicable – witness, for instance, Hotley Bottom Lane or Hobbshill Lane. The latter, uniquely, has survived as a ‘green’ track, still unmade-up, a time-capsule that enables one to revisit the lanes of old Prestwood as they were when the Parish Church was first built. The only threat to it is its recent designation as a "By-way Open to All Traffic", replacing its previous bridleway status, against much local opposition. The only other surviving green lane is Peterley Avenue, the old approach road to Peterley Manor, post-medieval and constructed in the times when manorial gentry went in for grandiose vistas along extended avenues of trees.

Farming

The second world war had a dramatic effect on farming, as it had on the rest of life. The war cut the country off from food imports from the Commonwealth and America, so that massive areas of new land were needed for cultivation to produce food. This totally reversed the decline in arable land and increase in pasture, so that the area under crops suddenly became greater than that under grass. Wren Davis’s farm was no exception, with an increase in wheat production, brought back from harvest in a donkey and cart. Virtually all the pine and larch woods (including Nanfan Wood and Lawrence Grove) were also felled for pit-props to use in the trenches.

Lawrence Grove 2013: in WWI the pines were cleared and it was replanted to beech.

Birches are re-colonising areas where the beech also has subsequently been felled.

This was, however, to be a temporary blip in the long-term trend. Economic forces were such that farming generally in this country, and particularly crop-production, was increasingly unprofitable, and trends prior to the interruption of the war were to re-impose themselves immediately the war was over. Indeed, despite the need for “home production”, farming remained financially precarious during the war. Massingham (1940) reports one farmer in Great Kingshill claiming “ he could not sell his pigs and cattle at rates worth their keep, that prices were worse than in the zero-year of 1938, that the cost of imported cake and fodder was ruinous for a small farmer … ”. Without the intervention of the war, however, Prestwood in 1950 would undoubtedly have been much poorer as a farming area, and for a few years there was still considerable activity on the farms. The orchards, too, also survived the war and were still frequent around the farms and breaking up the swathes of new housing near the High Street and Kiln Road.

While some agricultural land was lost to development, the nature of farming has continued to change and this has not been without its effects on the countryside and its wildlife. Continuing low profitability has encouraged some change of use, especially for those farmlands contiguous to the built-up areas. While some farmhouses have become private residences, their attached fields and orchards have predominantly been converted to gardens and horse paddocks. Regular stocking of horses in these fields has considerably reduced the range of wildflowers in favour of the coarse plants like dock and thistle and, at high levels of use, may gradually denude them of grass altogether. Intensive application of fertiliser, multiplied several times since the early 1970s, and sowing of higher-yielding cultivated varieties of grass (rye, cocksfoot, timothy) and clover can support higher stocking levels and greater productivity, but at the expense of the variety of plants and the usefulness of such areas for wildlife, leaving uniform green fields with low diversity of grass species and few flowers (and hence few butterflies), and less cover for nesting birds. Higher stock numbers on such fields and the possibility of turning them out earlier in the spring also increase trampling and general disturbance. Nationally, unimproved pasture declined by over 90% between the 1930s and the 1980s (Fuller 1987).

The decline of sheep-farming - although historically flocks had always been small in the parish - has led to the demise of a number of short-turf chalk grassland habitats where some of the Chilterns plant rarities were confined. An expansion of the rabbit population for some time counteracted this change, but the spread of myxomatosis in the 1950s decimated the rabbit population, allowing the growth of long-grass swards and scrub across many prime habitats. By the end of the century the number of rabbits was again large, but by this time some habitats had changed irrevocably, and a new epidemic, Haemorrhagic Disease, had invaded the area and rabbit populations are on the verge of taking another hit.

Another change in practice has been the shift from hay and root crops to silage as winter feed for stock. Silage involves the cutting of high-yield grass while it is still green, beginning as early as May; with faster-growing varieties of grass, several silage cuts a year can be made, whereas only one harvest of hay is possible, because of the long period of dry weather needed before it can take place, usually in late summer. With hay-making the dry grass can simply be stored in dry airy conditions and used over the coming winter as animal feed. With silage, the green grass is fermented in silos, creating a concentrated nutritious liquid feed, which may involve some run-off of toxic waste, although the latter is reduced if the grass is allowed to wilt in the fields after cutting. The use of silage results in better milk yields than the use of hay. The effects on wildlife, however, have been serious. As the grass is cut early in the year and then several times afterwards, ground-nesting birds are no longer given the chance to raise their broods, as they were in the case of hay production. This has resulted in the plummeting of the numbers of such species as skylark, lapwing and corncrake. (In the latter half of the C19th RL Stevenson (1875) referred to the Chilterns as the “country of the larks”.) It also reduces the usefulness of the meadows for the seed-eating birds and the many insects encouraged by the longer-term development of plant species allowed to flower and fruit.

With respect to arable production, increased use of fertiliser, herbicides and insecticides, along with new plant varieties, while improving yields considerably, have had serious direct impacts on wildlife use of cultivated fields and brought traditional cornfield annual plants to, or close to, extinction. Fertilisers have also avoided the need for rotation of crops and fallow, and this has decreased the availability of suitable habitats for wildlife of all kinds. The development of earlier ripening varieties of cereals like barley allowed for two crops each year, one spring-sown as traditionally and the other autumn-sown. This has meant that stubbles from summer crops are quickly removed in the autumn for the next sowing, instead of being allowed to remain through the winter, when they were a source of shelter and food for wildlife. Earlier harvesting of the spring-sown crops also reduced the time for corn-nesting birds to raise their broods before harvest, with the result that corn bunting in particular has come close to extinction as a breeding species in this country. Another problem with the more intensive use of arable land has been that the soil has been less capable of absorbing rainfall, so that at times of extended storms there is serious run-off that may cause flooding of neighbouring areas.

Cheaper, and earlier, imports of fruit from southern Europe in the 1960s, meanwhile, were a death-knell to the financial viability of the orchards, a fall in prices coinciding with rising labour costs. Most of the old orchards were therefore sold off for building land, while the rest lay unused.

The Stevens factory became one of the country's leading producers of cured bacon by the 1950s. It had a large workforce, including drivers for a fleet of vans, and served all the schools in the area. The pig slaughterhouse was a place of industry and great noise. After extensive refurbishment in the 1960s with the construction of a modern abattoir and being renamed Fine Meat Company, the factory produced bacon and pies. Consequently there was an increasing market for pigs, the rearing of which expanded from a side-line at the beginning of the 1960s to a peak of some 90 pigs a week, both “porkers” and “baconers” taken by tractor and trailer, eventually supplying much of London and the Home Counties. The company was closed, however, in 1972 with the loss of many jobs. A field to the east of the factory had been used in the sixties for ‘blood pits’ – deep well-like shafts, 30 or 40 feet down, for disposal of steel bins of offal. The field was later used as the playing-fields for Clare Road school (built 1966) and the pits had to be capped with concrete because the ground above kept subsiding into them. A grassy dell between Collings Hanger Farm and Prestwood Lodge was similarly used. When the Lovell estate was built across the land this area had to be left as open grass because it was unsafe to erect houses on it. It is now known as Greenside (Doel 2000). It was in these fields that the Stevens ran an annual Donkey Derby in the late 1960s and early 70s, which may have been the origin of the name of Donkey Path which ran through the same fields. The closure of the factory meant that pigs had to be taken ever greater distances to the nearest abattoir, eventually having to go as far as Cambridge “to become pork for Waitrose’s Welfare Farmhouse brand” (Davis 2004). It became increasingly uneconomical and now no pigs are reared on Denner Hill or any other farm in the area, despite a brief trial in the 1990s at Andlows Farm. The factory was bought by Farmer Giles Pork Pies, but that in turn closed in the late 1980s. Sheltered housing was built on the site in 1989, now named Giles Gate, handily situated for access to facilities in the centre of Prestwood. The butcher's shop across the road became Prestwood Farm to Freezer.

Farmer Giles factory c1980

Sheltered housing at Giles Gate that replaced the factory, 2018

One farm business that continued to thrive, however, was the rearing of pheasants on Denner Hill, expanded by Dudley Davis’s son Derek and currently managed by his son George. After the war 150,000 pheasants a season were being produced. “By the 1980s, the Arthur Davis Game Farm was the oldest in the country” (Davis 2004). The game-bird business survives to this day on fields at the north end of Denner Hill, although the original farm was broken into smaller holdings, the farmhouse and a few surrounding fields being sold off as a private residence, while Derek’s brother Richard and his wife Sue moved into nearby Rickyard Cottage, keeping a few fields as a smallholding, rearing Hampshire Downs sheep and poultry. “When Richard became secretary of [the Hampshire Downs] breed association and looked into the first flockbook of 1890, he discovered that his great-great-uncle, also Richard, had been a founding flockholder. So the circle closes” (Davis 2004). Richard and Sue, no longer full-time farmers, were now able to indulge their interests in nature conservation and habitat improvement, creating a new “millennium” woodland and digging a new pond, while restoring, with the assistance of Prestwood Nature, the old roadside pond that is still on their land.

Minor alleviation of some of these problems occurred in the final decade of the century, as a result of European common market policies and funding, in the form of local authority grants for set-aside, to allow the development of conservation headlands without loss of profit to the farmer. Such set-aside is often temporary, however, and more permanent uncultivated field-margins need to be developed. Traditional farming methods, relatively steady for centuries, allowed wild creatures and plants to adapt to prevailing conditions, but there was always a tension between the aims of farming (which needs to control ‘pests’ and ‘weeds’) and conservation. Rapid changes in recent decades have broken the uneasy truce and many farms have become deserts for wildlife, which is a tragedy for the latter in a countryside where wild habitats have become few and far between and farmland provides by far the greatest part.

Locally, the impact of such changes has been felt, but most farmers in the parish have fortunately been concerned to preserve traditional methods as far as possible and have not aimed for over-intensive production. Traditional hedge-laying, for instance, is still sometimes practised, as beside the Wren Davis fields, with the aid of the British Trust for Conservation Volunteers. Such holding on to tradition has allowed a few rare grassland plants to survive in some places, on pastureland or in hayfields. On the whole, however, arable "weeds" have seriously declined in variety, and the traditional farmland birds have plummeted in numbers. Prestwood has not witnessed the worst effects of modern large-scale intensive farming, but the countryside certainly holds a great deal less natural wildlife than it used to do.

The largest agricultural concern in Prestwood today is that started by Wren Davis. He formed a company, Wren Davis Ltd, in 1953, and its holdings spread from just north of Perks Lane in the south up to and including Nanfan Farm in the north, including most of the land between Wycombe Road and Hampden Road. The emphasis has always been, however, on quality of production rather than quantity and they have always tried to maintain a light touch as far as their impact on the countryside goes. Their pasturelands, for instance, remain largely unfertilised, and they bought up Nanfan Wood after witnessing the devastation begun there by modern forestry. Although silage is cut, some grassland is left to develop as a hay crop, more amenable to wildlife. The diversity of their output has, however, by force of circumstances declined, so that towards the end of the century they were specialising as dairy farmers, and grass and crop production was almost entirely for stock consumption. A pasteurising plant was built in 1952 at the dairy.

In August 1953 Wren Davis bought a Land Rover for his son Rex, who reported

I used my Land Rover daily to go out to the milking bail [hut on wheels for holding the cows while being milked] in the fields, while I milked the cows, then brought back the churns. I used it to move the milking bail on to fresh grass daily. Then I collected milk churns from 13 other farms in the trailer. … I have used it to take over 1000 calves to market in Aylesbury and other local towns. The Land Rover was also used for field work, including with the side rake … and the trailer. It was also used for moving heavy dairy equipment and the 18-ton ploughing engine. … Each Sunday I drove to Great Hampden for bell ringing, morning and evening.

This same vehicle was still in use, fifty years later.

The number of delivery rounds steadily increased with the building of new houses, and by expansion into new areas by purchasing other dairy farms. By 1962 they were one of the most modern dairy farms in the country, producing 4,500 gallons (36,000 bottles) a day of tuberculin-tested full cream pasteurised milk from a pedigree herd of 57 Guernsey cows, all bred at the farm by Rex Davis, using champion Guernsey bulls imported from other farms to prevent inbreeding. Milking in the field, rather than bringing the cattle into a cowshed, is more hygienic and kept the dairy clean from mud. Their own electricity generator helped ensure the dairy kept operating and the two large ‘cold rooms’ stay refrigerated, even if public supply were cut off. David Davis looked after the farm machinery and the fleet of 20-30 delivery vans, so that they were entirely self-sufficient as a business operation.

They supplied bottled milk and cream from a herd of a hundred cows to residents not only in Prestwood and Great Kingshill but also a major part of the central Chilterns: Great Missenden, the Chalfonts, Seer Green, Beaconsfield, Hazlemere, Holmer Green, Hughenden Valley, Naphill, Walter’s Ash, Princes Risborough, Marsh and Stoke Mandeville. They also supplied milk wholesale to other dairies at Downley, High Wycombe, Amersham, Princes Risborough, and Kensworth in Bedfordshire, as well as cartons of milk for shops and vending machines. Milk was collected from a range of farms, treated and bottled in a single day, ready for delivery to customers early the next morning. (Information as at 1998 supplied by Rex Davis.)

At the end of the 1900s, however, the dairy needed modernising and profits had become so poor that this would not have been economic. The Wren Davis farm, since 1999 effectively managed by David Davis’s daughter, Virginia Deradour, who had become a Director of the company, took the decision to discontinue their dairy herd. While still delivering milk locally, this now comes from a consortium of farms over a wide region of England. Meanwhile the farm became registered organic in an attempt to move into new market opportunities, as well as preserving the environmental value of the land. Specialist wheat varieties (Iron Age, Roman, medieval and Victorian) are grown for milling into flour, and pedigree Guernsey suckler cows are reared. (These are male calves suckled by their mothers until they are weaned and then sold on as “store cattle” to be fattened for beef. The female calves are mated as yearlings and sold on as pregnant heifers to become future dairy cows.) Free range turkeys are raised for local sales at Christmas time, while Tamworth pigs are reared in an enclosure in Lawrence Grove Wood. With the help of Countryside Stewardship, grants have been obtained for renewal of many of their hedgerows, the old orchard at Collings Hanger Farm is being restored with traditional varieties of fruit-tree, new trees have been planted in Prestwood Park and areas of semi-improved chalk grassland are gradually returning to a more original state. The orchard is grazed from time to time by cattle or, more recently, Herdwick sheep.

The old dairy was subsequently sold in 2012 to Malt Brewery, a new company making craft beers, that has built a solid distribution base to local pubs, and opened a shop at the premises. Supplementary income is generated by hosting school visits, including from schools in inner London, several times a week in the summer. This is an eye-opener for many children who today are increasingly insulated from contact with the countryside. Many think that meat comes from supermarkets rather than animals in the fields! The old barn, which is a listed building, is currently being carefully restored, using timber from the farm itself, to provide an office, classroom for school visits, and other rooms that will become a valuable community resource. Another building now hosts a fruit and vegetable retailer, N & P Fruits.

Rex Davis with his pet donkey. Photo by Virginia Deradour. Rex died in 2009.

Tamworth pig, Collings Hanger Farm

New tree planting by Wren Davis in Prestwood Park

Herdwick sheep belonging to Hampden Bottom Farm

Wood spurge and an old cherry tree in Nanfan Wood

Old hedgerow on Collings Hanger Farm being restored by re-planting

Old Napoleon Whiteheart cherry tree, Collings Hanger Orchard

The old barn at Collings Hanger shortly before restoration work was started

Old barn under reconstruction 2019

Mobile milking cow for school visits and classroom in barn behind

Apple Day 2009 at Collings Hanger Farm - open day with apple-bobbing and other activities

One new enterprise is Peterley Manor Farm, which maintains pick-your-own fruit fields, greenhouses for raising garden plants, a plantation of Christmas trees, and a very busy farm shop selling fruit, vegetables, local honey and other foodstuffs from their own land or local suppliers. This enterprise was set up by a newcomer, Roger Brill, in August 1982, starting from scratch at what had been a traditional farm. His great grandfather Edward had begun farming at Maidenhead in the 1880s. Roger studied horticulture at Writtle College. A number of traditional varieties of apple are grown for fruit and juices. He has also restored the old pond beside the footpath through his fields to its former glory, presided over by a fine large oak. Old ploughs once used on the land are exhibited in the car park just outside the shop, providing a resonant link with the past. Traditional methods of cultivation are used, avoiding harmful chemicals as far as possible, so that the farm is wildlife-friendly. More recently the business has expanded to include Wild Strawberry Café, run by Roger's daughters Katy (a chef), while two other daughters Philippa and Gemma help to run the business.

Peterley Manor Farm - shop and greenhouses, with display of old ploughs in foreground

Andlows Farm, refurbished from the proceeds of the sale of two fields just before the war, was purchased by the Garners in 1952, and they formed a company named Sevenex Farms. They added Nairdwood Farm in the 1960s. Joseph Garner died in 1994, when his son John (1923) took over. John Garner still lives there and has further enlarged the farm, so that it now extends along the whole east side of Prestwood from Rignall Wood to Neard Field beyond Nairdwood Farm. In the late C20th Andlows was largely arable, although John Garner experimented with keeping pigs for a few years. By the early 2000s the farm was becoming increasingly unviable. John Garner is now retired from active work and Ian Waller of Hampden Bottom Farm now manages his fields.

Waller rents most of the fields on the Hampden Estate, mostly to the NW of Prestwood, but including a few fields that encroach upon the parish to the west of Lodge Wood. Not from a farming background, he worked his way through agricultural college and first arrived at Hampden Bottom Farm in around 2000. He currently grows high-quality wheat (for baguettes), field beans (for export to Egypt to make houmous), and oil-seed-rape, and the farm is part of the government Environmental Stewardship scheme. Some of his fields have wide cultivated but unfertilised margins where rare cornfield annuals are managing to flourish, although these fields are just outside Prestwood parish. He has a small flock of Herdwick sheep which are used to keep grassland areas in good condition and also provide a modest income from selling meat. Over the last decade Waller has been gradually working towards a no-till method of managing his arable land, which preserves the soil ecology and conserves carbon, unlike traditional deep-ploughing. He has also radically reduced the use of chemicals. It is used as a demonstration farm by LEAF, Linking Environment and Farming, and receives visits from other farmers throughout the country to witness its pioneering work.

John Priest carries on his father’s beef cattle business at Ninneywood Farm, while also working with his wife Ann as a commercial photographer.

|

Fields at Honor End worked by Hampden Bottom Farm. Grim's Dyke ran along the fence-line but has long been ploughed out here |

John Priest in Grubbins Plantation |

View Cottage on the south side of Angling Spring Wood at the eastern end of what was left of Andlows Farm, just beyond the Prestwood boundary, was a two-up two-down annexe for a cowhand, Mr Bedford, who ran the dairy there and later Town End Farm in Great Missenden. John Garner sold this part of his land off in 1985 to another farmer, Paul Thompson, who kept herds of Charolaix and Aberdeen Angus cattle for stock breeding. He converted the cottage and dairy into a larger building re-named Angling Spring Farm and upgraded the private access from Great Missenden along Whitefield Lane. Thompson also bought Hobbshill Wood, bordering the Prestwood boundary along Hobbshill Lane, in 1994, when the High Wycombe furniture business that had owned it went bust, the last remnants of the old timber industry thus vanishing, and with it the economic worth of all the local woodlands. By 2000, however, Thompson also retired from farming and sold the farm on as a private residence, which was subsequently totally rebuilt.

Welsh rugby league international David "Dai" Davies’s family migrated into the area to take over Hatches Farm in the 1960s, where he continued the tradition of mixed farming, as did the Tuffneys at Cherry Tree Farm. David Davies, a parish councillor, retired in 2002 and now rents out his fields to others.

Following on from the surge of large-scale poultry farming in the early part of the C20th, turkey farming continues to be big business in the area, with large sheds at the new Perks Lane Farm (once part of Cherry Tree) from 1960 and just outside the parish boundary at Hoppers in Great Kingshill from 1949.

Hampden, Hotley Bottom, Honor End, and Pankridge Farms are no longer farms, but private residences, although the first two preserve some pasturage. Prestwood Common, Atkins and Sedges Farms are all horse-raising and livery firms, the fields converted into horse paddocks. Many of the fields abandoned by farming have also been converted into horse paddocks, including those run by Clemmit Farm beside Church Path.

Farm Survey 2005

In March 2005 questionnaires were sent to all farmers active in the area up to 3km from Holy Trinity Church, a region a little larger than, but including, Prestwood parish. This was conducted and published by the then Prestwood Forum for Farming and the Countryside (2005) and funded by the Prestwood Society. It was stimulated by a wider survey by the Chiltern Society (2005) that showed a continuing decline in the profitability of farming, and sought to establish the state of farming in the Prestwood area and how farmers were coping.

The farms responding ranged from 2.5 to 1,400 hectares, but were concentrated near the lower end (modal size 76 hectares). They varied widely in type from wholly or mostly pasture, through mixed arable and pasture to entirely arable, while one farm was devoted to fruit and vegetables (horticulture). The main products were beef cattle, milk, sheep, poultry/game, wheat and other grains, oil-seed rape, beans, fruit/vegetables, Christmas trees, and hay/straw. This exhibits a greater range than in the past, reflecting the need for farmers to diversify.

A third of the farms were supported by Countryside Stewardship (government grants now replaced by Environmental Stewardship), including two of the three largest (over 300h), but none of the smallest ones (up to 20h). Stewardship agreements covered an average of 53h per farm, or just over 10% of the total farmed area. All these agreements included the maintenance and restoration of hedgerows, three-quarters conservation headlands, and half a mix of chalk grassland conservation, uncultivated field margins, tree-planting, and non-rotational set-aside. Other measures included unimproved grassland, wildlife areas, orchard restoration and educational access. Farms were now therefore involved in an intentional way in conservation practices and this provided a significant part of their income. Two of the farms were registered organic, but none of the others contemplated going down this road, which was a difficult one for many, especially those raising crops, who were dependent on chemical inputs to maintain sufficient yields to be competitive.

Nearly 30% of farms had ancient woodland on their land, but this is no longer capable of supporting a commercial return. Two farms in the survey maintained some sort of active woodland management, but for the most part the woods were essentially unmanaged or hired out to people raising pheasants for shooting syndicates (doing substantial damage to the ground flora). On the other hand, five farmers in the survey had created new woodland or, in one case, re-created declining parkland, with the help of the government's Woodland Grant Scheme. One farmer said he did it because he "loved trees".

To maintain a good hedgerow needs regular management to preserve cover for wildlife, ideally cut every three years (so that fruit can be produced two out of three years). The commonest form of cutting these days, because quicker and less labour-intensive and therefore cheaper, is flailing. Done without due care, which is often so under pressure of time, this can leave damaged shrubs, jagged and half-severed branches. Most of the survey respondents resorted to flailing, the majority cutting hedgerows once a year, with only four leaving a three-year gap. The conservation ideal is to leave cutting for three years, thus giving two years out of three when wild fruit is available to farmland birds, but this enables the growth of thicker branches which increase the likelihood of damage when flailed. A third of farms had "gapped up" hedges by re-planting, and two had re-laid some hedges, a traditional practice which is now very rarely followed because it is so time-consuming and involves considerable skill.

Most farms had a pond or two, but only half had one that was well-maintained, as they have largely lost their economic function.

As most grassland these days has been fertilised at some time, there is little "unimproved" grassland capable of supporting a wide range of native plants and their associated eco-systems. This makes it imperative to maintain what has survived and to increase this resource by restoring more such grassland. Half of the farms had some unimproved pasture and those involved in Stewardship funding were maintaining or expanding these.

Old hay meadows, cut late enough in the year (end of July or later) for a rich mix of flowering plants to bloom and produce seed, have largely disappeared, either converted to pasture (especially for horses) or by being used for silage. Only four farms in the survey reported having a hayfield, and all of these were cut before the end of July.

There has been a massive decline in native farmland plants and wildlife in the last fifty years because of the widespread application of new chemicals such as herbicides, insecticides and fertilisers. Most, if not all, the farms could not have survived without employing these substances, although the two registered organic managed to keep these to a minimum using approved treatments compatible with biodiversity. Only one other farmer avoided the use of artificial fertilisers and other substances.

It would be easy to argue that farmers cannot afford conservation these days, and it is this that has stimulated governmental stewardship schemes, recognising that if conservation is to happen for the general good then it has to be paid for. In this context all respondents to the survey agreed with the statement "Farmers cannot afford not to be involved with conservation". Almost all also agreed that it is important in principle for native wildlife and plants to be conserved, even though farming inevitably involves some degree of destruction of natural eco-systems. It is a matter of balance, although where it comes to survival or not the balance may well be heavily in favour of basic economics.

Growth of Community Facilities

The growing population not only supported the growth of Wren Davis’s dairy business, and created a demand for other facilities like Peterley Manor Farm, but also gave rise to a growth of retail businesses and community facilities.

A new school for 8-11 year olds was built in 1966 at Clare Road within the Lovell Estate (and at least preserved one patch of grass as its playing-fields). Homes for the elderly, especially sheltered accommodation, were built in several areas, including the site of a smithy at the crossroads at the eastern end of the High Street, opposite the recreation ground on Nairdwood Lane, Bouquet Court and Dresser Road in the middle of the Lovell Estate, at the western end of Lodge Lane, and Giles Gate on the site of the bacon factory. The Lovell estate also included a community centre, a surgery and a few shops.

In the mid-sixties Prestwood appeared to be a growing and flourishing centre – “ Prestwood Is Growing So Popular ” exclaimed a headline in the Bucks Free Press on 26 November 1965 - with an increasing number of shops and businesses, especially on the High Street, and a regular bus service to Great Missenden and High Wycombe. Stevens’ bacon curing and pie factory was still operating then, selling pies and sausages in the butcher’s shop opposite as well as transporting them all over the region. Hildreths’ blacksmith and farrier business naturally came to an end in 1954, and the old forge was demolished, but Richard Hildreth extended the site on Wycombe Road by incorporating land belonging to the former house The Limes in order to create a garden centre, café, and ironmongery, as well as a shop selling china and glassware. The stone name plate from the old Limes has been built into the wall of the café, although the latter is actually on the site of the old forge, which was taken down in 1999. Richard himself still lives in the old flint cottage opposite the garden centre that was the home of William Hildreth back in 1850. Shops in 1965 on the High Street and Wycombe Road included a potter’s (Mike Casson), making crockery and vases on the premises, Wren Davis’s dairy, an off-licence, delicatessen, wallpaper/paint seller, another ironmongers (Howard’s), a bookshop, Jean Fowler babywear, electrical retailer, Dunkleys shoeshop, newsagents, H Hildreth’s gift-wear and dry cleaners, hairdresser (Judyth Hair Fashions), barber, chemist (Alec Rae), cheese-shop (Wixon & Gryckiewicz) and even a shop selling garage doors. The bakery and cake-shop was still using traditional ovens for home-baked bread and buns, the baker having to start at 1.30 am to be ready for early-morning customers buying their lunches to take to work. There were three butchers, three garages, and a coal merchants (AH Gurney & Son, established before the war) on Nairdwood Lane. In 1977 the local “Jubilee Committee Souvenir Booklet” listed 29 extent businesses. While many of those in 1965 had gone, they were replaced by new ones according to the times (DIY, estate agents, upholstery, country sports equipment, men’s and ladies’ clothes, a bank, florist, removals).

In 1951, when Clement Attlee ceded the government to Winston Churchill, he retired as the first Earl Atlee to the newly extended Cherry Cottage in Prestwood, at the corner of Green and Nairdwood Lanes, having lived for six years previously at Martinsend Lane, just outside the parish boundary, where his garden ran down to Angling Spring Wood.

Mr and Mrs Clement Attlee with their daughter at a reception in the

village hall. Mr Attlee is lighting a

cigarette for his daughter Felicity. Prestwood. Jan 1952 ( Photographer: Ronald Goodearl, Bucks Free Press)

Apart from Earl Attlee, local writers JHB Peel (The Bield, Hotley Bottom Road) and Clement Shorter (Chiltern Manor, off Martins End Lane), and broadcasters Steve Race (Martins End) and Ronald Coleman (Great Kingshill), also lived in the parish or just outside it. The celebrated potter and designer William Rupert Newland came to live in Prestwood in 1954, dying there in 1998 at the age of 79. Born in New Zealand he had studied painting at the Chelsea School of Art after the Second World War and then took up pottery, teaching at the Central School of Art and Design 1949-1982. He exhibited in London in the 1950s and did interior designs for coffee bars. His wife Margaret, née Hine, who he married in 1952, was also a potter and taught in London and then High Wycombe School of Art (1971-87). Another Prestwood-based artist (who lives in a cottage on Nairdwood Lane, not far from Clement Atlee's residence) is Jo Dollemore, who trained at Wycombe School of Art and became a graphics designer and now concentrates on paintings mostly in acrylics.

A week-long carnival was organised in September every year by the Prestwood Village Hall Committee in the post-war years, but this was eventually abandoned. A “Donkey Derby” was held in one of the Stevens’s fields off what is now Lodge Lane in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Queen Elizabeth II’s Jubilee to mark her accession 25 years earlier provided the occasion for another carnival, on 7 June 1977. This started with Morris dancers at Chequers Parade at 2pm, followed by a “mystery entertainment” in the High Street car park. Everyone then moved on down the High Street to the Green Man car park for a display by the Diamond School of Dancing. At 3.15pm a procession started from here, led by a Pied Piper and the Morris dancers, along with the Middle School Recorder and Drum Band. It went back along the High Street, down Wycombe Road as far as Sixty Acres Road, which was followed into Honor Road. Here there was a children’s street party from 4 to 4.30pm before they moved on to Prestwood Common (recreation ground) for an hour of entertainment by a Punch and Judy man and a magician. (Information from the Prestwood “Jubilee Committee Souvenir Booklet”. This booklet also gives a glimpse of the culture of the times, listing issues and personalities that local people felt were important in 1977. These were: Strikes, inflation, wage-differentials, men in space, emergence of conservation, Peter Scott, cars, TV, “teenagers”, End of Empire, Common Market, Benjamin Britten, Michael Tippett, Coventry Cathedral, National Theatre and Laurence Olivier. An eclectic mix reflecting national concerns of the time, but, interestingly, with no local flavour at all. If anything symbolises Prestwood's evolution from isolated rural village to a community fully linked into national, and even international, contexts, this indubitably does so.)

There are still a good number of community events - an annual Prestwood Big Lunch in June on Prestwood Common, including music, stalls, displays and games; the switching on of the Christmas lights at Chequers Corner; the Chiltern Steam Rally each July (under the inspiration of David Davis, who has a fine collection of these old machines at Stony Green) and Bonfire Night, both on Wren Davis fields; and the biennial Spirit of Prestwood Fête on Prestwood Common in May.

Prestwood Society was founded in 1971 to look after the interests of all Prestwood parish residents in matters such as building development, highways and traffic management, and the environment. It also provided social activities, talks, visits and walks. It emerged from attempts to stop building on green land to the south of Prestwood. Beginning in 1996 it organised the production of a Millennium Map of the parish, with contributions from local artists, which was duly erected in Prestwood Village Hall in 1999 and remains there to this day as a marker for the future of how the parish looked at this time. Due to lack support the Society was wound up in 2015, but it was replaced by a more modern web-based enterprise, Prestwood Village Association, formed in 2013. Although the Prestwood Society by its constitution covered the whole parish, including part of Great Kingshill, a Great Kingshill Residents’ Association was founded in 1988 to cater specifically for the residents of that area, extending beyond the boundary of the parish and including Little Kingshill, reflecting the fact that the inclusion of part of Kingshill in the parish in 1850 never really made any social sense. They produce a regular Village Newsletter. In addition, since 2007 a local enterprise has issued a community newspaper HP16 The Source, covering the HP16 postcode, which includes Prestwood and Great Kingshill. Funded by advertising and donations, it is delivered free to every household in its area by volunteers.

In 2003 a local nature conservation group calling itself Prestwood Nature was formed in an attempt to preserve the remaining green space and wildlife of the area. Although it reaches more widely than the parish, Prestwood is at its centre, and parish sites with which has been actively involved include Prestwood Picnic Site; the restoration of various ponds, such as Sheepwash, Kiln Corner, Brickpits, and in Lodge Wood; hedgerow restoration on Denner Hill; Angling Spring Wood (outside the parish but adjacent to its boundary); Holy Trinity churchyard (internationally important for its community of waxcap fungi and now a Local Wildlife Site) and creation of a community orchard and demonstration wildlife garden by Greenlands Lane allotments.

If the influence of religion has much declined, the churches still remain a centre for much social activity. Holy Trinity Church provides playgroups, a youth club for the 9-12s, a choir, and a Sunday creche. It has also published the biannual Trinity Herald since 1989, serving then as a village newsletter for the parish, being delivered free by church members to almost 3000 homes in the area. Since its function as a community newsletter has been superseded by the secular HP16 The Source, it now focuses much more on church matters, although it is still delivered free to all homes. Prestwood Methodist Church provides a youth club, parents and toddlers group, and coffee mornings. The churches also organise many special events, such as a large pageant in 1999 to celebrate the sesquicentenary of Holy Trinity. There are also inter-denominational groups like the Bridge Youth Club and Lighthouse, which organises a holiday activity week for children in the summer. A group calling itself “The Friends of Holy Trinity” formed in 2002 and organised a “Spirit of Prestwood Fête” on 3 May 2004, which was a great success despite the best attempts by the weather to turn the site at Prestwood Common into a sea of mud. The fête has been held biennially ever since.

Some of the public houses retained for a while a community character, especially the Green Man, which is involved with sports teams and charity fundraising. The Travellers Rest had a pool team until it closed in 2013 and was replaced by residential housing. The two schools in the parish also organise fêtes that are well-attended.

A lot of community groups are specifically for women – three women’s institutes (evening, morning and afternoon), Ladies Circle, Ladies Self Defence (which meets at the Red Lion Public House), National Womens Register, Ladies’ Monday Group, a mother and toddler group and two aerobics groups at the Prestwood Village Hall.

Some other groups are for young people – Scout and Guides units, playgroups, Great Kingshill Under 5s, Young Farmers Club and a Youth Club. It remains a problem that there are few facilities for teenagers in the area, and public transport to surrounding towns is infrequent. There appears to be no greater provision for older persons, either: Age Concern, Pippin Club and a Forget-me-not Club (social activities for the over-60s) are the only groups active in the parish.

The Sports Centre on Honor End Lane (named Sprinters) was first built in the 1970s on land that was previously part of the Howard brickyards and subsequently used in the war for storing military equipment. It was rebuilt in 2002 for £1,176,000, with grants from the national lottery, Chiltern District Council and Great Missenden Parish Council, as well as local fund-raising, and opened in 2003. There are also a number of sports associations for badminton, basketball, cycling, karate, long distance walkers, dancing, angling, football, cricket, netball, tennis and yoga. Clay pigeon shoots take place from time to time at the old Brickfields (where, until ten years ago or so, there also used to be scrap-car racing). Other activities are also served by the Chiltern Traction Engine Club, flower club, gardening society, theatre club, Ramblers’ Association, budgerigar society and a whist drive. The noted local painter Jo Dollemore also teaches art classes.

The Village Halls at Prestwood and Great Kingshill provide the essential venue for many of the above groups. Prestwood Village Hall hosts the Millennium parish map and contributed its own commemoration by adding a new clock-tower in 2000. A Community Centre recently opened at Prestwood Common, managed by the Great Missenden Parish Council.

Horse-riding is a major local leisure activity, supported by a number of local riding schools, livery stables and horse-breeding farms (Prestwood Common, Sedges and Hatches Farms). David Bright, who lives in Prestwood and breeds horses at Clemmit Farm beside Lawrence Grove was a director of the National Pony Society 2007-2009.

There is support for special groups, such as the disabled (Prestwood Community Action), NSPCC, Northern Ireland Project (organising holidays for Ulster children aged 11-13 in and around Prestwood), the Chiltern Breast Cancer Support Group (activities at the Chiltern Hospital in Great Missenden) and various medical charity fundraising groups.

There are six Neighbourhood Watch groups in Prestwood itself, as well as a Horsewatch group.

Although its geographical remit is much broader than Prestwood, the Chiltern Society has also made a huge impact on the area. It has helped to make residents more aware of countryside issues, as well as its more specific achievements in terms of commenting on planning proposals, protecting ancient buildings, restoring water flows in rivers, clearing out ponds, and looking after the interests of walkers. With respect to the last, it has maintained oversight of the condition of all public paths, cleared them when necessary, erected stiles and way-marked all routes clearly. They also ensure that all the paths are walked regularly. This has resulted in the Chilterns having a network of public footpaths that is better than any other part of the country. Most of these paths are ancient ways that should be preserved as part of our historical heritage, let alone as facilities for ramblers. Prestwood shares fully in the benefits of all this activity and is criss-crossed by a good network of footpaths and bridleways.

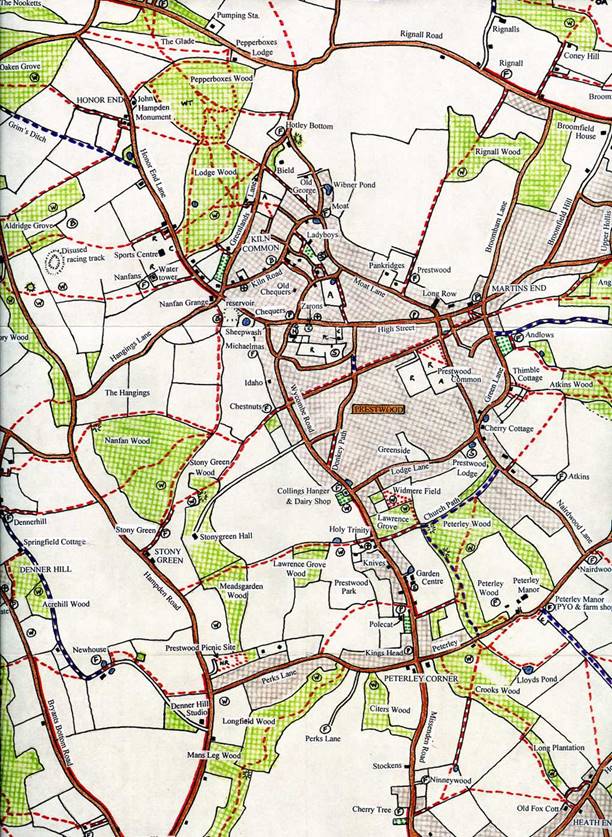

Footpaths (red) and bridleways (blue) in central Prestwood parish.

Extract from "Walkers' and Riders' Map" 2003 (originally published by the Prestwood Society).

Updated copies of the whole map are available from Prestwood Nature at £2 per copy.

It is ironic that the largest building boom and increase of population that had ever occurred in the parish, in the 1960s-1970s, with most of the new population having no traditional ties to the area, coincided with the start of a decline in the economic and social energy that had so burgeoned for two decades after the war. No doubt it only reflected an inevitable long-term trend, in which the terrible deprivation of the war years and the bounce-bank of the recovery years was just a blip. The number of facilities available in the centre of Prestwood failed to grow with the population and steadily declined. The three garages along the High Street are now reduced to one garage and there is no petrol station. (Another garage at Heath End, which was there in 1950, has also been demolished.) Many of the shops and commercial facilities have gone – the bank, two butchers, small grocers, confectioners, and other specialist shops. Christine and Roger McNicol’s bakery on the High Street once served 700 people on a Saturday, but finally closed its doors in 2001, after having survived a hundred years. For some goods there are fewer outlets now than there were in 1850! Remaining shops are concentrated at Chequers Parade and nearby, although the modern "green" café and refill shop Pantry 51 opened in 2020 at the other end of the High Street.

Chequers Parade 2019. The main shops here are an Indian takeaway, flowers, fish-and-chips, hairdresser, charity shop, and post office-cum-newsagents. Nearby are a butcher, two small supermarkets, estate agents, dry cleaners-cum-keycutting, chemist, building society, doctors, dentists, and opticians.

Both the White Horse and the Royal Oak pubs in the Great Kingshill area have been closed, the former demolished to make way for a small up-market housing estate at Heath End, plus the Travellers Rest in Prestwood, while several pubs have had major reconstruction work carried out with inevitable loss of character (Chequers, Polecat). The chain running the Chequers planned to change its name, a move vigorously opposed by local residents, but showing the loss of local connection that is part of the modernisation process. In the end a sort of compromise was reached with the name "Chequers Tree", but it is still known locally as Chequers.

Old outbuilding at The Chequers, 2000, demolished during reconstruction

Royal Oak, Missenden

Road, Great Kingshill, 1993 [Photo JH Venn, loaned to High Wycombe Library.]

The remaining pub in Kingshill, the Red Lion, is now a popular restaurant. There are fewer pubs in the Prestwood parish of 2000 than there were in 1850 and ten times the population! Will these survivors manage to maintain their character against the forces of modernisation and uniformity on which economic survival seems to insist, or will they go the way of John Betjeman’s “Village Inn”:

Ah, where’s the inn that once I knew

With brick and chalky wall

Up which the knobbly pear-tree grew

For fear the place would fall? …

And where’s the roof of golden thatch?

The chimney-stack of stone?

The crown-glass panes that used to match

Each sunset with their own?

Why did the community fail to thrive as the population grew? The answer lies in a phenomenon that existed as far back as the C19th, but which has grown in importance with time. We have already seen how the economy of Prestwood was always dependent on outside markets. The lace-making and straw-plaiting came and went at the whim of urban women’s fashions. What the farms produced depended on the demand from the larger towns and cities (and more lately the world economy). The growth of the orchards occurred as communications improved, particularly the railways that enabled fresh-picked fruit to get to the London shops by the next day. The decline of wood-turning (bodging) paralleled the collapse of the furniture industry in High Wycombe. The

only woodworker now is Malcolm Hildreth, who, like his father, learned his woodcarving skills in the High Wycombe chair factories, and still practises from home. He carved the posts that mark the "audio trail" through Angling Spring Wood, just east of the parish.

|

Malcolm Hildreth at work |

One of the carved posts in Angling Spring Wood |

The dominance of London has grown as communications have become ever more efficient. Nowadays it is possible for people to live in Prestwood and work in London. The population of the parish, having more than doubled between 1900 and 1950, more than doubled yet again between 1950 and 2000, mostly with commuters to London and others working in nearby towns like High Wycombe, Amersham and Aylesbury. These new residents, for the most part, have no traditional links with the land or the locality. Many of them spend little time there – working, shopping and spending leisure time outside the parish. With most households having cars, there is little demand for local facilities, and local shops in any case can hardly compete with large out-of-town supermarkets that are able to negotiate lower prices by using their economic muscle and simplify shopping for the time-pressured by offering large ranges of goods in one place. Home deliveries of milk (although supplemented by deliveries of a range of other goods nowadays) faces stiff competition, with many people preferring to buy cheaper imported milk from the supermarket than have it delivered to the door. The quality and freshness of local produce can be higher, but many people are willing to sacrifice these values to expediency and economy. Expectations of choice are also much greater – through modern communications we have seen the world and we want it all. One small community cannot begin to provide the range of goods and services now demanded, and the self-sufficiency of the village is therefore gone forever. It is not just that it cannot compete: it is simply not even necessary. The village becomes associated with lack of choice, whether it is in job opportunities, goods for consumption, services, with whom one associates, or opportunities for leisure, including the very country environment itself.

As a result the local economy is spiralling downwards with the better-off residents largely shopping elsewhere and local shops relying more on poorer and elderly customers. Local businesses depend for survival on extending their markets well beyond the parish. Thus the dairy delivers milk in regions as far away as Henley; the garden centre and the farm shop depend on motorised customers from far afield; public houses like the Polecat, Red Lion, Chequers, and Gate depend less on local people drinking and socialising so much as providing meals that attract customers from a wide region, including surrounding towns. The "local" is no more.

Places

What was left of Winifred Peedle’s wildflower site had become a dump during the second world war and continued as a car scrap-yard afterwards. This scrap-yard was set up by Graham Britt, a former bus-driver from London, to deal in used caravans and cars. He planted a small apple orchard and kept goats, for which he planted comfrey as fodder. According to the reminiscences of Aileen Catterson, whose family owned land above this site (e-mail to Prestwood Nature 2019), "Old Britt" was a " very large, jovial man who always gave me 6d whenever we visited him. He lived with his wife ... on the site in a caravan. ... I think it might have been an old Traveller's caravan - I remember sitting on the flight of wooden steps leading up to the door. There were always dozens of cats and kittens everywhere. ... The story went that Old Britt never had permission to use the land as a scrapyard. Eventually the powers that be took him to court and he was told to clear the site. Old Britt was never wealthy and on his own would not have been able to achieve the clearance. He was subsequently fined ... £10 a day for each day the scrap remained on the land. ... I never heard what happened to Old Britt. I assume the debt mounted up and up until he was forced to vacate the site, leaving the land as settlement for the fine. " The site was thus acquired by Wycombe District Council in 1976, and cleared of rubbish to construct a picnic site and nature reserve (although the odd hubcap or engine part can still be found as a reminder of its history, as can the comfrey plants introduced to feed the goats). It is now managed on behalf of the flowers, butterflies and other wildlife, which are all remarkable, but many of the old glories, especially the rarer orchids, have probably gone for good. It is now managed on lease by the Chiltern Society.

Prestwood Picnic Site seen from Denner Hill to west, Perks Lane housing development on right

Peterley Manor was eventually sold by the trustees of Charles Walter James, fifteenth Baron Dormer, for £14,250 in 1951 (Coulon 2000) and converted into three residences. Some of the early structures survive inside, as well as the remains of the walled garden, a well, the detached row of cottages where the coachman, gardener and so on used to live, and the lodge at the entrance of the drive from the road, although this was substantially destroyed by fire a few years ago and has had to be rebuilt.

Prestwood Park House, after being a hotel until 1952 (when the tenant, a Mr Lehman, alias Layman, was imprisoned for non-payment of his rates) was let as a staff hostel for St David’s College, a private school in High Wycombe. It was eventually sold in 1960 as a residential home for the elderly, before being converted once again to a private residence around 1983/84 by the builder Mr Soden.

Prestwood Lodge was eventually bought by the County Council and demolished so that a new residential school for children with special needs could be built on the site.

Prestwood Lodge School 2006

The only new architecture of any aesthetic note during this whole 50 years in Prestwood was the building alongside Green Lane of Quilter House designed and built by Peter Aldington (born Preston 1933), with his wife Margaret, in 1965-66 for local businessman Mr Quilter. To quote Pevsner and Williamson (1994), this private house constituted “… an exciting combination of classic International Modern forms (flat roof, horizontal balconies, circular stair-tower, free plan) and tactile natural materials (timber, rough brick, slate) that appear Scandinavian or American in character .” While one might question how balconies could be anything other than horizontal, this is clearly a remarkable new building which, if it is not grounded in the local ecology, is at least a symbol of the international character of the modern age. Aldington was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright. He describes his work thus : "Experiments with breaking down the inside-outside barriers were made at the house in Prestwood. Here we defined two categories of space - those which require privacy ... and those which could be more 'open' and less well-defined. The private spaces are enclosed ... The more open spaces weave between ... Sliding glass walls open on to a water garden, partly covered by the overhanging first floor, which acts as a transition between inside and outside, leading the eye from one to the other and inviting a journey ..." (Aldington 2000). This was Aldington's first major commission; he went on to gain an international reputation and was awarded an OBE in 1986, when he retired from practice. English Heritage listed the house as Grade II in 1999, remarking that " the harmony of the timber frame, partitions and flooring is exceptional ". Unfortunately the house stands well back from the road behind high hedges and is difficult for a member of the public to appreciate. It is popular as a venue for film and television productions.

Quilter House 2013

Very few of the buildings of 1850 remain to the present day, so that the old aspect of low whitish flint cottages is now replaced by red brick, depriving the village scenically of its special character. Most people today would not want to endure the cramped, dark conditions of the 1850 worker’s cottage, although some have been sensitively renovated and amalgamated to make up-market modern residences that preserve the old aspect on the outside (like Thimble Cottages in Green Lane). Most of the farm buildings of old survive, but many were converted to private residences as the smaller farms became uneconomical and were sold off. (Remaining buildings from the nineteenth century or earlier are listed in Appendix IV.)

In my beginning is my end. In succession

Houses rise and fall, crumble, are extended.

Are removed, destroyed, restored, or in their place

Is an open field, or a factory, or a by-pass.

Old stone to new building, old timber to new fires,

Old fires to ashes, and ashes to the earth

Which is already flesh, fur and faeces,

Bone of man and beast, cornstalks and leaf.

TS Eliot "East Coker"

Abandoned footpath, Brickfields