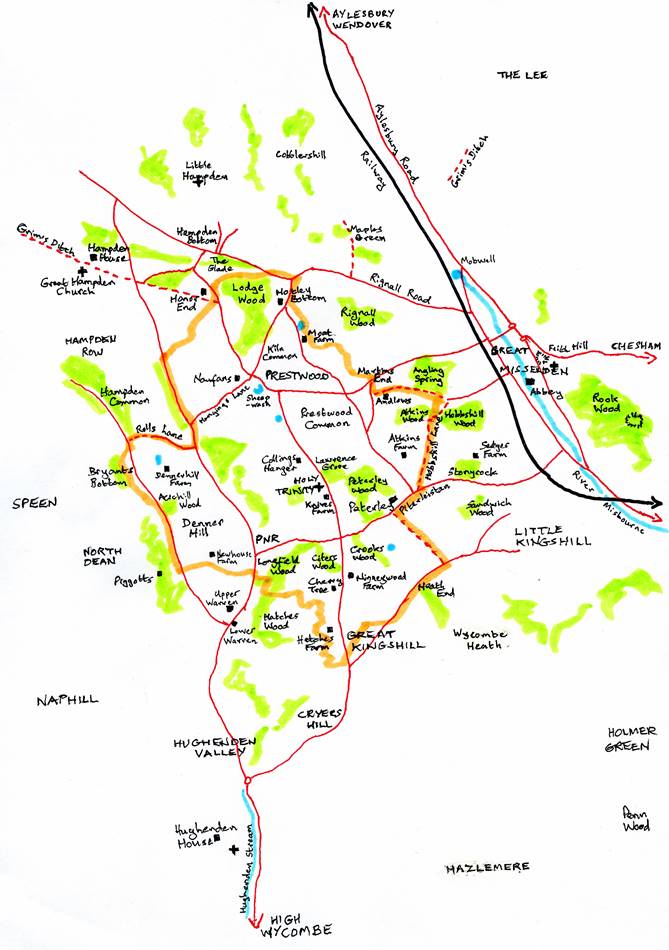

SCHEMATIC MAP OF PRESTWOOD PARISH AND SURROUNDING REGION

Key: Boundary of parish in orange. Selected roads in red. Woodland green. Ponds and rivers blue.

PNR = Prestwood Nature Reserve (Prestwood Picnic Site)

Part I History of the land and its people before 1850

1 Introduction

Prestwood 570ft. above sea-level, has a church built in 1849. It is the centre of a high plateau full of pleasant woods and bottoms.

That is the entire entry for Prestwood in “The Little Guide” to “Buckinghamshire” (1950).

There is, however, much more that can be said about Prestwood than that it has a church, woods and bottoms. In fact Prestwood, as is mentioned, did not even have a church for most of its history, the few residents having to tramp miles to reach those at Great Missenden, Great Hampden, or Hughenden. The Episcopal Parish of Prestwood (it has never been an administrative parish) was constructed in 1849 from parts of three existing parishes (Great Missenden, Hughenden and Stoke Mandeville).

Prestwood gets its first known mention as Prestwude in the Cartulary of Missenden Abbey (which held much property in the area) in 1184. For most of its history Prestwood was a small hamlet, a mere scattering of farmsteads and peasant cottages hidden away on the crest of the Chilterns. As you travel from the Midlands to London, after passing Aylesbury and its dull clay plain whose dark grey mud clings to your boots in great clods if it’s wet and it usually is, you suddenly meet a steep scarp where the ancient chalk was once uplifted to slope away more gently like a ramp to the south-east. Here, in what was officially designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in 1964, is a world of dry chalk valleys and clay-capped hills, plentiful woods, and a mixed agriculture where small fields and hedgerows have survived, if not totally unscathed, at least less scathed than elsewhere. The mix of fields and trees coupled with undulating hills creates the scenery for which the Chiltern Hills are famous.

As Prestwood squats on a small plateau you are not immediately aware of all this. You have to go to its northern boundary to get an excellent view across the farmland of the Hampden Bottom valley, or to its eastern border to look over the ancient landscape of Great Missenden, or to the west side of the settlement where you can look over the valley running from Hampden to Wycombe to the imposing ridge of Denner Hill that defines the parish’s extremity in that direction. To the south the plateau only gradually falls away to Great Kingshill, and beyond there to the Wycombe conurbation, and provides no grand spectacle. If you ignore the mysterious Celtic tribes that sparsely inhabited these heights before the Romans came - the “Ancient Britons” – the main settlers, the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons, the Normans, chose the valleys for their habitations, affording ready water, fertile soil from river sediments, and easier travel between communities. So the Prestwood plateau was largely left uncultivated, woods, scrub, heath (“wasteland” as they were denigrated), the uncolonised outback, and there were no ancient settlements, as the Celts left no evidence of such behind, except for the striking rift called “Grim’s Ditch”.

To the east lay the manor of Great Missenden, an early Anglo-Saxon valley settlement established beside the River Misbourne. At this time the stream probably began further north than it does today, when it first issues (when it runs at all) at Mobwell, beside the Black Horse public house. It was always a winterbourne, however, and would often dry up in the summer. Nowadays it is usually dry all winter, too, but at the time of Anglo-Saxon settlement the water-table was higher and the stream could issue with considerable force, regularly flooding the riparian meadows, such that the monks at Missenden Abbey, who farmed here, saw fit to erect a sluice-gate just east of where the village started in order better to regulate the flooding. The fine silt brought down by the stream was the source of the excellent fertile alluvial soil that made this an excellent site for farming. The Mobwell spring was augmented by a series of similar springs all the way down the valley, so that sometimes the river flowed from a point lower down even when it was dry at source. Alternatively, when the water table was particularly high, the river actually ran from springs north of the Mobwell, further up the valley along which the road to Wendover runs, and occasionally a stream would run along the valley occupied by Rignall Road today, as evidenced by patches of gravels along this route. (It is recorded that in the early 1670s a stream exceptionally ran one year from Hampden Bottom, and not again until the spring of 1764, after six months of continuous rain.) The original manor house is now lost, but was almost certainly on the slopes to the east of the village, where there are still remains of fortified medieval settlements, as at Frith Hill and a larger one in what is now Rook Wood. The former seems most likely, although it is quite a small steep mound, as it is close to the current parish church, which was probably built on the site of the original place of worship. As at nearby Great Hampden and Hughenden, settlements of similar antiquity, the convenience of the lord of the manor was of much greater consideration than that of the bulk of the villagers who lived some way away. On the higher slopes the manor and the church were safer both from flooding and from marauders coming up the valley.

To the north of Prestwood, and close by it, was the ancient Priest’s Wood from which it took its name, an hour-glass-shaped wood descending steeply to Rignall Road. Just south-east of the wood, lay a little cluster of cottages that was for most of its history the nucleus of Prestwood, although later its centre of gravity was to shift further south. The cottages bordered an expanse of communal land known as Kiln Common (from the brick-earth dug there for brick-making), which in turn connected on the south side to the huge Prestwood Common, itself stretching south to the monks' farm at Peterley. Beyond the common lay a few more farms and a cluster of houses making up the little of community of Great Kingshill, themselves clustered at the edge of another large common that stretched to the vast wild Wycombe Heath and what is now the start of the High Wycombe conurbation at Hazlemere. A small cluster of cottages to the east of Great Kingshill and on the edge of Wycombe Heath was appropriately named Heath End and was also incorporated in the new parish.

To the west the land again plummets down to a valley between the Prestwood plateau and Denner Hill, a southern extension of Hampden Common. There were just a few early farm settlements on the crest of Denner Hill, which got its name from denn 'swine-pasture', indicating that the clearing for the first farm here left plenty of the old woodland where hogs could be let out in late summer to forage for acorns and beech-mast. Both Denner and the northern part of Great Kingshill were eventually to be incorporated into the 19 th century ecclesiastical parish of Prestwood, although they were quite distinct communities that tended to look away from Prestwood, towards Hampden in the case of Denner, and towards Hughenden in the case of Kingshill.

These tiny communities were to remain relatively unchanged right up to the middle of the nineteenth century, and the great woodland, now renamed Lodge Wood after the later lodge built below it that governed access to the private ride to Hampden House, survives to this day, although much of the other original woodland has become more depleted. The Common, too, survived up to 1850, but only minute remnants exist today, their character changed entirely from the wilderness of gorse and scrub with patches of rough pasture, marsh and ponds that once characterised it, now being in use as allotments or recreation grounds (as happened too at Great Kingshill). The name “Priest’s Wood” derives from its having the benefice of a priest to the Great Hampden Estate, which once covered much of this district (while Missenden Abbey supplied the priest, their own lands were more to the south, around Peterley, or to the east at Martin's End). The priest lived and farmed (for he would have had to keep himself in those days) at Honor End, an outpost on the boundary of the Hampden Estate, and on the west side of "his" wood, both his fields and certain rights in the use of the woodland being conferred as part of the benefice. The oldest parts of the current buildings, now converted from a farm into private residences, date back to the C16th.

Prestwood was thus only a small part of the ecclesiastical parish that was to take its name (still often referred to as Priestwood at the time) when it was officially consecrated in 1852. The church was built almost precisely in the centre of the new parish, but hardly near any of the little communities then existing, having just a couple of farms and inns as neighbours. This may have been convenient for the provision of food and drink to the first vicar Thomas Evetts, who had a splendid vicarage built hard by the church, but less meaningful to parishioners, most of whom would still have had to walk a mile or so to worship (although far closer than their previous parish churches). When the first school in the area was built next to the church, it must also have seemed a mixed blessing – no longer a long journey down the steep hill to Great Missenden, but hardly on most people’s doorstep either.

The medieval manuscripts in Missenden Abbey refer to Peterley, Honor, and Kingshill, and there were farms scattered in other parts. Peterley was a manorial estate leased by Hugh De Noers family to the Abbey shortly after its foundation in 1141. It lies to the south of Prestwood Common and is dominated by Peterley Wood, partially felled and drained to create farmland, and the ancient way of Piterleistan that transverses it from Great Missenden to Great Kingshill. Although partially cleared as the name indicates (ley denoting a clearing), there was still much "wild" land, as the Abbey was granted by the Crown "free warren" in 1302, that is, a licence to hunt animals. At some time after the dissolution of the monasteries in 1541 it reverted to the king and granted to the Dormers (who already had the manor of Hughenden, including the church). A manor house was erected here for Geoffrey Dormer, but it was normally leased to lesser gentry. Around it was established a small community of farms and workers or servants of the estate. It went into decline in the C18th, and the house fell into decay, being replaced by a “small plain new house” (Lipscomb, 1847) not long before the founding of Prestwood Parish. The vegetable garden and granary survive of the earlier house, as well as carved Tudor chimney-pieces incorporated into the new building. It was still, by most standards, a substantial property, and was divided into three homes in 1951 when it was sold off by the Dormers.

It is strange that this little community surrounding Peterley Manor was closer to the new Anglican church than any other community in the parish, when the Dormers themselves were Catholics! Their tenants, however, may not have been of that religious persuasion, and certainly the gentleman living in Peterley Manor at the time of the founding of the parish “made one of the largest contributions - £25” to the appeal to finance the new church. Proximity to the grandest house in the new parish would have lent some kudos to the church, and there was always the excellent excuse of being plumb in the physical (if not social) centre of the parish. (Another site for the church had been offered close to the community north of Prestwood Common, where most people were concentrated, but that was not taken up – it would, of course, have been a trek of two miles from the southern tip of the parish at Great Kingshill.)

Hatches Farm at Great Kingshill, formerly right at the edge of the common itself before it was whittled away by the enclosures, is one of the oldest farms in the parish, dating back certainly to medieval times and probably beyond, although nothing so early remains in the present structures. Honor End remains to this day, until recently a working farm, and gave its name to the road that passes it, Honor End Lane. Some of the other farms dotted around also have long pedigrees – Andlows (also Anglers), giving its name to Angling Spring Wood just outside the parish boundary, was probably Martin's Farm run by Missenden Abbey, which gave its name to Martinsend Lane running down to Great Missenden; Atkins (or Adkins), which lent its name to Atkins Wood; Ninneywood and Cherry Tree (earlier Fry’s) at Great Kingshill; Nanfans; Hotley Bottom; and (K)Nives and Collings Hanger Farms, either side of the church. The origins of most of these names are lost to us now. Many incorporated family names of ancient owners, and they were often altered as properties changed hands. Nanfans, sited originally where the house called Nanfans Grange now stands, not at the modern building of Nanfan Farm to the west, was quite possibly the first farm in what was properly Prestwood, for it would easily have been settled from Hampden and it is surrounded by some of our most ancient hedgerows, indicating that the fields here were laid out in early Anglo-Saxon times.

The frequency of “wood” in these place-names reveals an essential and enduring feature of the parish. It is part of the traditionally wooded Chilterns and even today many substantial fragments of the ancient woods survive – Lodge, Peterley, Nanfan, Crooks, Citers, Longfield, Atkins, Acrehill, all have ancient pedigrees. Many of them are fundamentally the same shape as shown on maps of the C17th, and were probably that way centuries before. These woods, all highly managed, were planted mainly to beech in the C19th for the furniture industry in High Wycombe, the large town to the south, and provided employment to many local people, including the “bodgers” who felled and worked young beech into chair-legs. Before that they would have been a mixture of oak, beech, hornbeam, ash, birch, rowan, whitebeam and others. In medieval times the extent of woodland was probably greater than it is today, but the antiquity of many of the farms shows that the parish has been a mix of woodland and fields for centuries, and, until the mid-C19th, heathy commons as well. Despite C18th enclosures, the extent of Buckinghamshire commons was estimated at 97,000 acres in 1794.

Prestwood today has retained some of its rural nature, despite the huge growth of population in the latter half of the C20th, which completely changed the character of some parts of the parish. It remains a typical example of the Chilterns countryside, farmed and worked for centuries, shaped and reshaped by the hand of man, but still with a place for nature and (though more rarely nowadays) quiet contemplation. At Prestwood Picnic Site (a local nature reserve) you can sit among a riot of colourful flowers, with a refreshing view across the valley to Denner Hill, from cowslip time in the spring, through the time of the orchids and many other plants in the summer, to the Chiltern gentians in the autumn. It may have lost a lot with the ravages of history, including having been at one time a scrapyard, but it still has great charm. At toadstool time in the autumn you can walk through ancient woods that abound with many more species of fungi than you can name. In one group of fields in summer bloom a thousand plants of a particular umbellifer (a low plant with sprays of tiny white flowers, a relative of cow parsley) that grows nowhere else in the county - botanically Oenanthe pimpinelloides or Corky-fruited Water-dropwort, but best referred to as "Prestwood Parsley". Quiet lanes in spring can be a joy to walk down, the hedges abounding with the red-white-and-blue of foxglove or red campion, stitchwort, and bluebell or germander speedwell, plus spikes of yellow archangel and, more rarely, the subtler colours of green hellebore and moschatel.

There are, however, threats to all this. Prestwood has been marked in the past by a degree of endurance through a myriad changes, industrial, economic and agricultural. But its resilience may be at the limit. Traditional farming is no longer profitable (it had always been marginal on the thin chalk soils - Plot,1676, quotes the Chiltern proverb that "chalk Land makes a rich Father but a poor Son") and huge changes in land use are imminent; they have already started, and they are a cause for concern. We are lucky in that local farmers are for the most part responsible and sensitive, but sheer economics may be against them, and one sometimes shares the feeling that John Betjeman expressed in his poem “The Dear Old Village” on the passing of traditional village communities:

He takes no part in village life beyond

Throwing his refuse in a neighbour’s pond

And closing footpaths, not repairing walls,

Leaving a cottage till at last it falls.

Some of our hedgerows are a thousand years old or more, but many have been increasingly neglected over the last century and are becoming fragmented. There are trees that have stood for two or three hundred years, but trees that found a convenient spot to flourish in ancient times may suddenly find themselves in the way of man’s “progress” centuries later. Once there were getting on for a hundred ponds in the parish – no more than a dozen or so qualify for a second glance today, and they depend on continual nurture by those who own or live near them. Residents are less dependent on the area than they have ever been in the past. Many work outside the parish, largely in London. They have greater mobility, and electronic communications free them from restraints of distance. As a result they are both less aware and, in many cases, less concerned, about their local area than earlier populations would have been. This history shows that there always has been change, and of one thing we can be sure - there is much more change to come.

Great Hampden Church - St Mary Magdalene

Great Missenden Church - Saints Peter & Paul

Hughenden Church- St Michael & All Angels